This week I read various articles on the 1998 peace accords between Ecuador and Peru, including a chapter from Fisher and Shapiro’s Beyond Reason, a journal article from Peaceworks, and a journal article from Boundary & Territory Briefing.

These are my notes and quotes, primarily from Beyond Reason, which I found the most insightful for my purposes. If you’re interested in a detailed historical background the Boundary & Territory Briefing article is what you’re looking for. The Peaceworks article has more on the various factors that led to (and away from) agreement over the years, as well as US-specific information.

I wrote my key takeaways from these articles for the subscribers of my Future of Conflict series.

Beyond Reason – Jamil Mahaud Chapter

Jamil Mahaud, former President of Ecuador, authored this chapter.

Background of intractable conflict:

Since the early nineteenth century attempts to reach a solution consistently failed. The countries had tried war, direct conversation, and amicable intervention by third parties, mediation, and first-class arbiters including the King of Spain and President Franklin Roosevelt. None yielded a positive result.

Necessary factors to an agreement:

- Belief. There would have to be the popular belief that the war could be resolved. Myths are almost impossible to debunk; the intractability of the problem with Peru had deep roots in Ecuadorians’ flesh and souls.

- Civic participation. Making peace between Ecuador and Peru would have to be a “people’s project,” not a government issue. There would need to be a boost in participation of the people represented by any legitimate organization or group.

- Trust. Cooperation and mutual trust would need to be elicited from all sectors in this fragmented country.

- Political support. A formula for peace would need to be created. It would have to be acceptable for both countries and for many different sectors in each country.

- Economic stability. There would need to be ways to bring economic stability to a country on the verge of war. In such a moment of distress, how could the government go about dictating badly needed, but unpopular, economic adjustments that would compromise the national unity and governability of Ecuador?

- A clear, coherent, comprehensive action plan. The resulting plan would need to be not only military but also economic, political, and international in scope.

Then they meet, and the question comes up, how to get to know each other?

Fishers advice: lay your own cards on the table

They establish a mutual goals: end the conflict

And a mutual milestone:

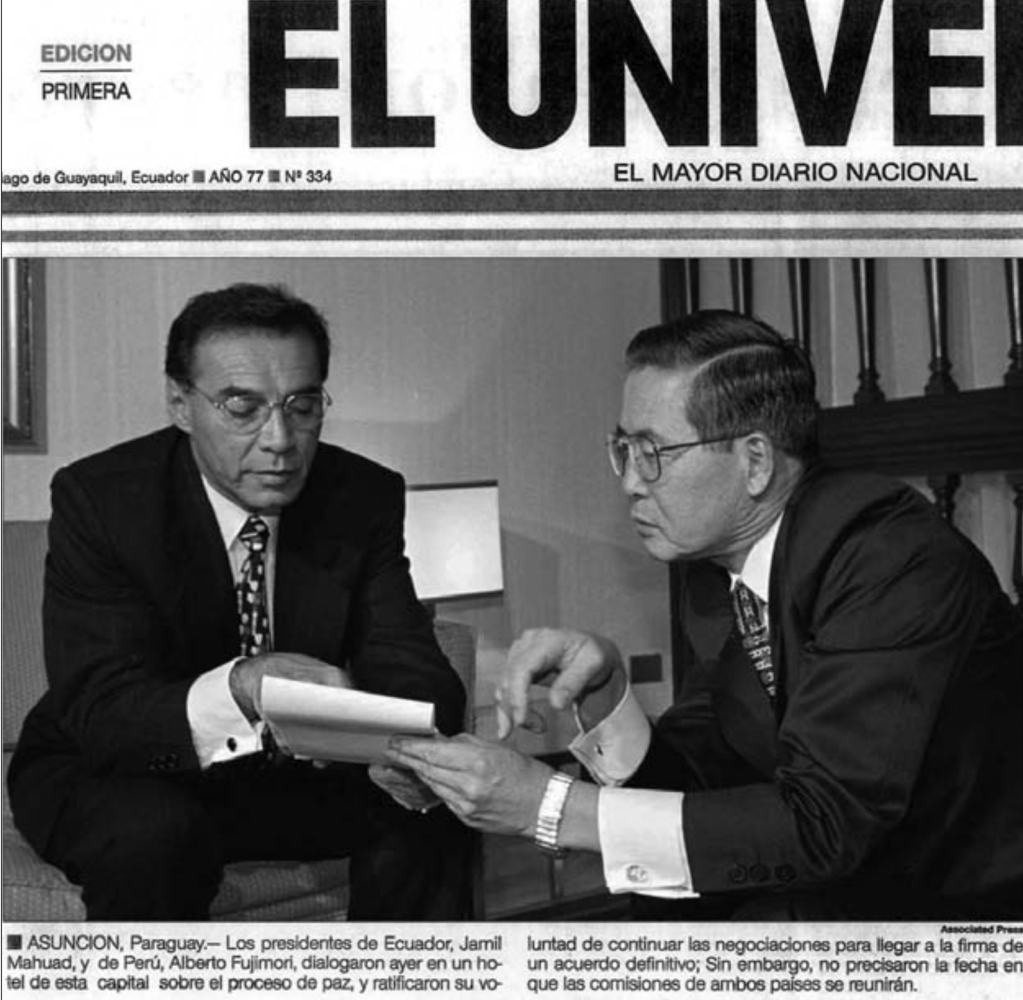

President Fujimori and I agreed that a goal should be to have the public in each country come to see that we were working together, side by side, toward the settlement of the centuries-old boundary conflict.

The opposite of losing face -gaining commitment. Gaining face?

I told Roger that I knew the photograph was intended to influence the public. What surprised me was the extent to which the photograph also influenced President Fujimori and me. Looking at the photograph, President Fujimori said that the public in each country would now be expecting us to settle the boundary. We had publicly undertaken that task, and we owed it to the people in each country to succeed.

It costs nothing to acknowledge the obvious:

I said, “President Fujimori, you’ve been president for eight years. I’ve been a president for four days. You have negotiated with four of my predecessors. I would like us to benefit from your extensive experience.” I asked him, “Do you have ideas on how we might deal with this border dispute in a way that would meet the interests of both Peru and Ecuador?”

Multiple negotiations at once:

Each would have the task of bringing his own constituents to accept a settlement of the boundary. I saw my role as leading two simultaneous negotiations. One role, obviously, was as negotiator with President Fujimori. The other role, not so obvious but equally important, was my role as a negotiator with the people of Ecuador, its institutions, and representative organizations.

They share this challenge:

Therefore, I proposed to him we not do anything to harm each other’s legitimacy as authorized representatives of our peoples. For instance, it would have been self-defeating to claim that a treaty was good for Ecuador because it was bad for Peru—or vice versa. On the contrary, I saw that the role of each president was to demonstrate that an agreement was good for both countries, good for the region, good for trade, good for economic development, and good for the alleviation of poverty. We needed a win-win proposition. In crafting that proposition, our roles were both stressful and full of personal meaning.

How popular support was helpful

We kept the people of Ecuador permanently informed about the advance of our negotiation. As progress was evident, a virtuous circle replaced the old vicious one. Negotiation became popular and openly a part of our national objectives. Participation increased. Everybody wanted to be part of the process and to express their voices. Common goals enhanced trust. Political actors started giving support because they understood gains were larger than risks if they represented the now popular will for peace. Belief in a negotiated solution replaced the usual pessimism. Overwhelming support at all levels of society boosted the government’s initial action plan. Although this peace process did not stabilize the economy, the menace of war no longer worsened the economic situation.

The Famous Photo

Boundary & Territory Briefing Article

Ronald Bruce St. John. “The Ecuador-Peru Boundary Dispute: The Road to Settlement.” Boundary & Territory Briefing, Vol. 3, No. 1. (1999) pp.34-5

Peaceworks Article

Beth A. Simms. “Territorial Disputes and Their Resolution: The Case of Ecuador and Peru.” Peaceworks, No. 27. (1999) p.12