These are my notes and quotes from Part I of Healing Resistance by Kazu Haga. I wrote my key takeaways from the book for the subscribers of my Future of Conflict series.

Intro

On learning the difference between civil disobedience techniques that happen to be non-violent and philosophical nonviolence:

I realized during that workshop that the stuff I had been teaching at nineteen wasn’t, in fact, nonviolence. It was nonviolent civil disobedience. I had been training people to go into mass demonstrations without throwing a punch. While that is certainly one application of the theory of nonviolence, I realized how limited of an understanding I had. If nonviolence is simply a set of strategies and tactics that does not use physical violence, then the Ku Klux Klan could argue that they are using nonviolence when they rally. Neo-Nazis could argue that they are using nonviolence when they march. And that doesn’t feel right. Something about the work of nonviolence has to be fundamentally different from the work of the KKK or neo-Nazis.

So it’s not about social change strategies. What is it about?

Fifty years after his assassination, Dr. King has taught me that a commitment to nonviolence is a commitment to restoring relationships and building Beloved Community: a world where conflict surfaces as an opportunity to deepen in relationship, a world where all people understand our interconnectedness, and a world where—as stated in the Kingian Nonviolence training curriculum—“all people have achieved their full human potential.”

Nonviolence as an ethical choice stems from a deep understanding about the impact that violence has on all people—those who experience it, those who perpetuate it, and those who witness it.

This is also key to my understanding of Gandhi: he could see (and respond to) the effects of violence on everyone involved. The “perpetuators” are also victims.

Kazu’s quest is to find the dialectical synthesis between movements of social change and movements of personal development. He believe’s he’s found that in nonviolence. Here’s his critique of social change movements he’s been a part of:

Many activist movements have the courage to put their bodies on the line and the militancy to shut down highways, occupy government buildings, and resist and blockade injustice in its tracks. Yet, I find too often that the very cycles of harm that we are trying to fight get replicated within those same movements.

I have known too many people who have been traumatized in one way or another in social justice spaces. From large organizations like Amnesty International to the smallest, most grassroots groups, people are getting harmed by a “woke” activist culture that has become toxic.

We can bring down the entire system and have a worldwide revolution, but if we haven’t healed our traumas and learned how to be in authentic relationship with each other, we will corrupt any new system we put in its place.

What makes real personal transformation possible? Once we know the answer, we can set up strategies to make it more likely:

In my work in prisons, I’ve had the privilege to witness the transformation of countless people who have committed the most horrific acts of violence—including homicide—into the most compassionate, dedicated peacemakers I know. I’ve had the honor of witnessing healing dialogues between people whose lives were brought together by tragedy. Between the person who almost beat another to death in a mugging and the survivor of that crime. Between mothers and the people who took away their children. Between two men who killed each other’s best friends. I have come to believe that if these depths of healing are possible on those scales, then there is no conflict that is too large for us to transform. In each of those cases, it has been through love and understanding, not shaming and punishment, that transformation was made possible.

While he’s critiquing resistance, he’s not critiquing the need for resistance. Rather, he (and I!) want it to be done in a way that includes everyone involved in the circle of concern:

We need resistance. We need to resist injustice, we need to resist violence, we need to resist our own tendency to fall into blame, resentment, greed, hatred, or despair. But we need to do it in a way that is healing to everyone.

Bringing in Uncle Marhsall on violence, as part of Kazu’s quest to empathize with those who employ violence (whether they are members of criminal gangs or members of the police department):

As ineffective a strategy as it may be, violence is oftentimes an expression of a yearning to heal. It is a cry for peace. As Marshall Rosenberg says, “violence is the tragic expression of unmet needs.” Needs for healing. Needs for release. Needs to be seen or to be heard. Needs for pain to be legitimized.

Violence may not always be the most effective strategy to meet those needs, but some of us don’t have access to strategies that might work better.

So he’s not a priori against violence, but looks at it analytically and asks, “What are the limits of violence as a tool?”

Violence does have its place. It is often an expression of unheard and unseen pain, and it can keep us safe. All that said, violence is limited in one very important way, and that is that violence can never create, restore, or strengthen relationships.

Violence can never bring us closer to reconciliation or closer to Beloved Community, which, in a principled approach to nonviolence, is always our long-term goal. If we’re ultimately not working to heal relationships, communities will always be at odds, and the threat of violence, injustice, and domination will continue. Any peace we create will be temporary.

Chapter 1

We’re confused when nonviolent tactics don’t work or people don’t fully get it. But we have unrealistic expectations of how much training is necessary:

We held a workshop once inside a unit in a county jail that exclusively housed war veterans. One of them told us that no matter what background they came from, each one of them had to go through a boot camp that lasted at least six months before being sent off to war.

The military invests heavily in training and in preparing their troops to use violence effectively.

Yet in many of my own experiences with movement work, we were trying to bring about fundamental shifts in society but only asking people to show up for a two-hour workshop the day before an action.

I began to see how unprepared we were for building the type of movement that I dreamt of.

We need to balance awareness of intergenerational trauma with something hopeful, or we’re doomed:

If we carry intergenerational trauma, then we also carry intergenerational wisdom. Like the trauma that has been passed down from our ancestors, their wisdom and resiliency is also embedded in our genes and in our DNA.

Chapter 2

Success story of institutionalizing nonviolence:

My first direct experience with institutionalizing nonviolence came in 2010 through my relationship with Tiffany Childress-Price, a teacher at North Lawndale College Preparatory High School, located just a mile from where Dr. King lived during his days in Chicago.

The neighborhood of North Lawndale where Tiffany teaches has struggled with generations of violence, and the school’s campaign to bring nonviolence to their two campuses started around the time that Chicago was getting national coverage for particularly high levels of violence. In the first year of their campaign, the school was able to reduce the rate of physical violence at their school by 70 percent at the height of the violence epidemic throughout the city.

How did they do it? By institutionalizing nonviolence.

The entire faculty was trained in nonviolence as part of their professional development, and they have refresher courses every other year. A group of student leaders receive a forty-hour training to become youth trainers every summer. These student leaders lead workshops for their peers throughout the year. The entire incoming freshman class receives a presentation on nonviolence by older students. Announcements about nonviolence are made over the PA systems.

The school got rid of their metal detectors and security guards and instead invested the savings into their students’ education. They track days without any incidents of physical violence, and after so many consecutive days of peace, students are rewarded with ever-increasing prizes such as a DJ in the cafeteria, no-homework days, and a community BBQ. Nonviolence became as important on campus as math and science. It was embedded within the policies, practices, and culture of the entire school and became part of what the staff and students do day to day.

Key takeaway: Major amount of initial effort and sustained attention.

What if professionals had as much training in nonviolence as they did in violence and control:

It takes consistent training to change old habits and conditioning. It takes consistent training for something to become muscle memory. We need systemized and institutionalized structures to support our practice. Imagine if every schoolteacher was given training in restorative justice, conflict de-escalation, mediation, and trauma response. Imagine if our police academies mandated undoing racism and nonviolence workshops for every new recruit.

Chapter 3

Another historical success from the civil rights movement in Nashville:

The leadership of the Nashville chapter of the sit-in movement included Dr. LaFayette, Diane Nash, John Lewis, Marion Barry, C.T. Vivian, and James Bevel—people who would go on to become the backbone of the Civil Rights movement. How is it possible that one chapter of one movement that had hundreds of chapters produced so many important leaders?

Spoiler alert: it was the training.

The leadership of the Nashville movement had been rigorously trained in nonviolence by Rev. James Lawson, an African American Methodist minister who had gone to India and studied the nonviolent tactics, strategies, and philosophies of Gandhi. The trainings simulated the types of violence the students might expect by sitting at lunch counters designated for “Whites Only”: insults, food being thrown at them, and even physical assaults.

Their training lasted for months.

He then draws an extended metaphor between nonviolence and martial arts:

The word “kung fu” does not actually refer to the Chinese martial art. Derived from the Chinese word gongfu, it refers to any skill that can be gained through consistent practice and dedication.

Why do we have such high and rapid expectations for learning nonviolence?

No one goes to a four-hour karate seminar and thinks they’ve “got it.” It takes years of dedicated practice for skills learned in karate training to be useful in real-life combat situations.

Similarly, if you think you can sit calmly at a lunch counter while people throw pies in your face, call you the worst insults imaginable, and physically assault you and your friends without having trained for it, you are deceiving yourself. For most of us, our natural reactions to violence fall into one of three categories: to fight, flight, or freeze.

Nonviolence gives us an alternative way of responding: to face.

Facing means looking your assailant in the eye, not backing down, not giving into fear, and not reacting in kind. Facing also means genuinely listening to your partner when they are upset, hearing their pain, and taking full accountability for your actions without blaming or getting defensive.

That might be one of my favorite ideas in the book. We have all these inbuilt reactions to trauma (fight, flight, freeze, fawn, etc). But we can train ourselves (observation without reaction) to behave differently, with a lot of practice.

Facing takes consistent practice, just like any form of martial art. True martial artists practice their art almost every day.

There’s another aspect of nonviolence we tend to get wrong, and that has to do with grammar:

Another reason for using the martial art analogy is because I don’t believe that one ever becomes nonviolent. Dr. King wasn’t nonviolent. Gandhi wasn’t nonviolent.

You and I are never going to become nonviolent, for the same reason that if you are a practitioner of karate, you never become karate.

Meditators don’t become meditation. Going to yoga classes doesn’t make you yoga. These are not things to become, but practices and lenses through which to view the world and skill sets that we utilize throughout our lives. It is a worldview and a practice, not a destination.

Nonviolence should be viewed similarly. Not as something to become, but a worldview and a skill set in which we are trying to improve in. It is through the consistent practice of the art of nonviolence that we are able to build up our nonviolent muscles so that they may become useful in our daily lives. That is why nonviolence is the martial art of transforming conflict.

Chapter 4: Violence

Most of this chapter is about how bad most definitions of violence are, as they historically have rested on the notion of physically hurting other people.

He looks at all the non-physical versions of violence (there are plenty) and all the violence involved in hurting oneself (there are 3x as many suicides as homicides every year).

Four definitions of violence:

- From The World Health Organization (WHO):The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, which either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation.

- In Kingian Nonviolence:Physical or emotional harm.

- From a child in a nonviolence training:Violence is painful.

- Marshall Rosenberg:Violence is the tragic expression of unmet needs

Chapter 5

There’s a nice public service announcement here about the different connotations of non-violence vs. nonviolence. It’s subtle but deep.

If there is only one thing I want readers to take away from this book, it is this: The idea that nonviolence is about “not being violent” is one of the most common and dangerous misunderstandings that exist.

This is why, in Kingian Nonviolence, we make a distinction between non-violence spelled with a hyphen, and nonviolence spelled without a hyphen. “Non-violence” is essentially two words: “without” and “violence.” When spelled this way, it is an adjective that only describes the absence of violence. As long as I am “not being violent,” I am practicing non-violence.

Nonviolence — what Gandhi calls ahimsa — is an active force for change. Gandhi calls it the most powerful, active, and courageous force in the world.

Nonviolence is not about what not to do. It is about what you are going to do about the violence and injustice we see in our own hearts, our homes, our neighborhoods, and society at large. It is about taking a proactive stand against violence and injustice. Nonviolence is about action, not inaction.

Kazu also makes a useful distinction between different kinds of peace. There’s a peace that’s the absence of conflict because one side gave up fighting. And there’s another peace which means that the underlying tensions have been resolved.

Johan Galtung calls “negative peace,” a peace that describes the absence of tension that comes at the expense of justice.

Dr. King went on to say that, “peace is not merely the absence of tension, but the presence of justice.”

So you can have a “peaceful marriage” or “peaceful occupation” because one side is so overwhelmed there is no question of dispute. But it’s not the kind of place anybody really wants to live.

Kazu then notes that “disturbing the peace” is exactly what is called for if you want to go from negative peace to positive peace. He prefers to call it “disturbing complacency”:

Dr. King was arrested twenty-nine times in his short life. Many of those times, he was charged with “disturbing the peace.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., civil rights leader, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, a man now used as a moral compass for this nation, was charged by the United States government for disturbing the peace.

This still happens today to many activists. When we use nonviolence to confront violence and injustice, we are not disturbing the peace, we are disturbing complacency. We are disturbing the normalization of violence. We are disturbing negative peace.

Chapter 6

Kazu give two typologies of conflict here. I didn’t find the first super useful so I’ll focus on the second, as it sets up a “measuring system” for nonviolent skill.

He says there are 3 levels of conflict: normal, pervasive, and overt:

Normal Level: A normal level of conflict happens as a result of daily life pressures—traffic, bills, or minor disagreements about where to go to dinner. They are an unavoidable part of our lives, and none of us get through one day without experiencing some normal conflict.

At this level, you can often take a deep breath and get through your day. If a friend is experiencing normal levels of conflict, you can give them a hug or suggest they take a deep breath, and they’ll be fine. You can easily prevent the conflict from escalating any further.

Pervasive Level: This is where you can feel the tension in the air, where it feels like one wrong comment could lead to a fight. This is the level that you can begin to see, hear, and feel the conflict beginning to escalate. Those warning signs are critical to notice.

People begin to raise their voices or stop talking. People start to call each other names. In interpersonal or group conflict situations, they use words like “You always do this,” or “You never do that.” Body postures change. You can feel your blood warming.

Overt Level: This is where conflict comes into full bloom. An overt conflict doesn’t necessarily have to be physical. But at this level, real harm is being done. The overt level of conflict is the transition point between conflict and violence.

The best thing you can do now is to manage the conflict. Stopping the immediate harm becomes your priority, even if it requires a limited amount of physical force. In an interpersonal conflict, we may need to separate the two parties. In an international conflict, we may need to enforce a ceasefire. We need to let things cool down so that you can begin dialogue again.

I find the 3 levels useful because of the following statement:

As a conflict escalates, our nonviolent response has to escalate to match its intensity. The higher the level, the more training and expertise is required in our response.

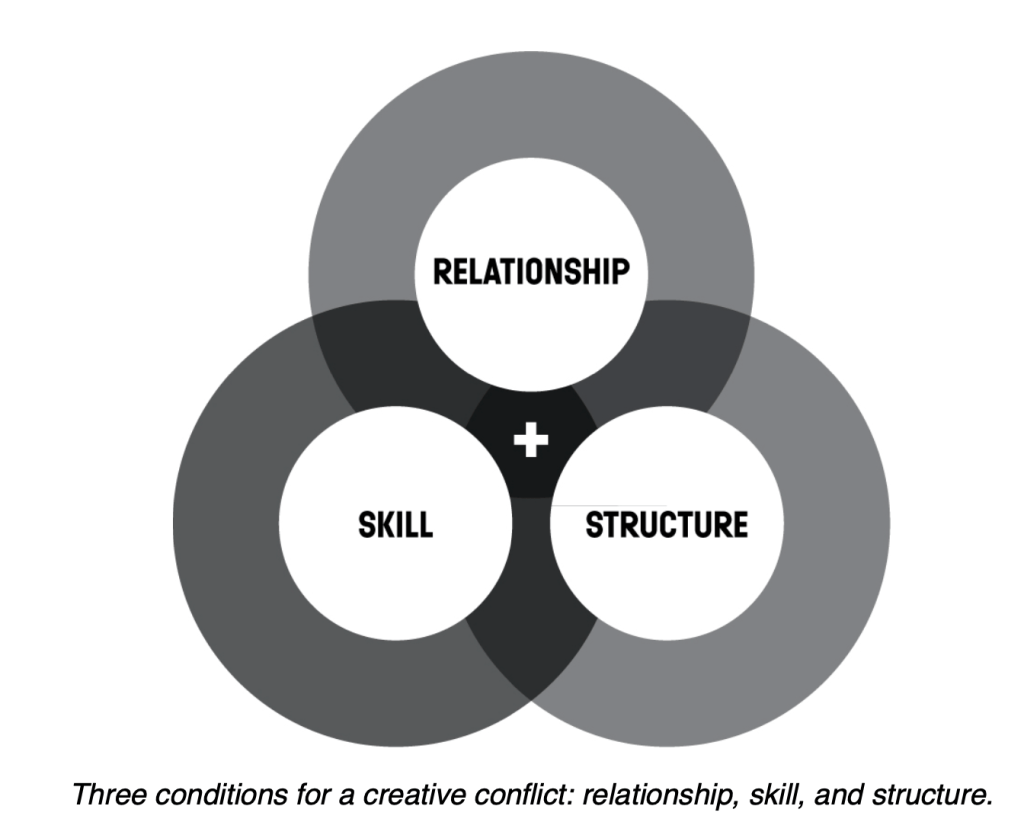

Speaking of the level of skill needed, he shared the follow diagram from Miki Kashtan:

To get the juice out of a conflict in a productive way (what we’re all trying to do, presumably), it’s good to have at least 2 of those factors.

Kazu is biased towards skill and relationship, and imagines that with enough training and dedication, people can mediate their own conflicts:

Structures, policies, systems, and bureaucracies are often an attempt to compensate for a lack of trust and relationships between people.

Chapter 7

One practice I have adopted is to listen to conservative podcasts and read right-wing papers and books by authors I may have significant disagreements with. As I listen, my focus is on trying to find what I do agree with or to understand why they believe what they believe. This way, when I find myself in conversation with someone who has different views, I can help us to find common ground—the starting place for creative resolution.

What I found most interesting about this practice is how he links it back to martial arts:

I consider this practice like sparring sessions in a gym. It’s not real fighting, but it gives me practice for real-life conflict situations. Listening to someone I disagree with on a podcast prepares me to have conversations in person with a greater level of understanding and empathy than I might otherwise. It has been enlightening to realize I don’t disagree with everything a conservative talk-show host has to say. It has been humbling to listen to their criticisms of progressive worldviews and policy proposals and realize I agree with some of what they say.