These are my notes and quotes from Swiss Democracy: Possible Solutions to Conflict in Multicultural Societies by Wolf Linder and Sean Mueller. I condensed my key takeaways for the subscribers of my Future of Conflict series.

Quotes from Swiss Democracy: Possible Solutions to Conflict in Multicultural Societies

The goal of the book is to examine the origins and function of the rather unique way democracy has been implemented in Switzerland, and then to see what we can learn from it in the quest to improve modern democracies.

The purpose of this book is not to heap praise on the Swiss way of doing politics and try to ‘sell’ its democracy. No system is perfect, even if some do seem a little less imperfect. For despite the many advantages and mechanisms that make Switzerland appear as a success story, there remains room for improvement.

They start by counseling patience and highlight that getting the institutional balance right takes lots of iteration over long time frames.

Swiss citizens want the exact same things as those of other countries: good jobs, healthy lives, sustainable economies and a solidary society… All that is different is the political structure in which these same goals are pursued. If ever there was one general lesson to be drawn from the Swiss case, it is probably that finding the right institutional structure takes time and will never be finished once and for all.

Of course, that only works if the starting institutional structure allows iteration!

The authors claim it does in Switzerland. Even better, they claim it serves both stability and iteration:

… one of the main Swiss paradoxes: its democracy both maximises stability and institutionalises openness. How is that possible? Stability happens by letting all important groups participate in collective decisions, either through political parties and governmental or parliamentary representation; interest groups voicing their concerns in the pre-parliamentary phase; social movements building up pressure from the street; or cantonal and local governments running their own show. At the same time, the system is incredibly open: a good idea, a determined organisation, some resources, and maybe fortunate circumstances allow almost anyone to change the Constitution or bring the entire political and economic elite to its knees.

I really like that linkage of political stability to decision-making, because I think it applies to any relationship:

Stability happens by letting all important groups participate in collective decisions.

There are three main features of Swiss Democracy I learned about:

The authors claim the unique character of Swiss Democracy is a result of a combination of these mechanisms:

It is the combination of power-sharing and direct democracy that puts the Swiss system at odds with much political theory and mainstream political thought. In contrast to other countries like The Netherlands, for instance, Swiss consensus democracy is not the result of negotiations among the political parties after elections but a permanent institutional constraint due to the referendum. In the US, direct democracy is not practised at the national level as in Switzerland, nor has it led to power-sharing in its individual States. And while elections to parliament are the decisive element in the competition between government and opposition in the UK and New Zealand, they have no such effect in Switzerland. Thus, the same institutional elements may function differently in different contexts, which is why it is important to look at them as a whole.

I’ll have sections for quotes regarding each of them.

I’ll also have sections for:

Then I’ll paste large quotes (whole pages) on:

- Comparison of US and Swiss direct democracy mechanisms

- Authors’ insights for multicultural democracies.

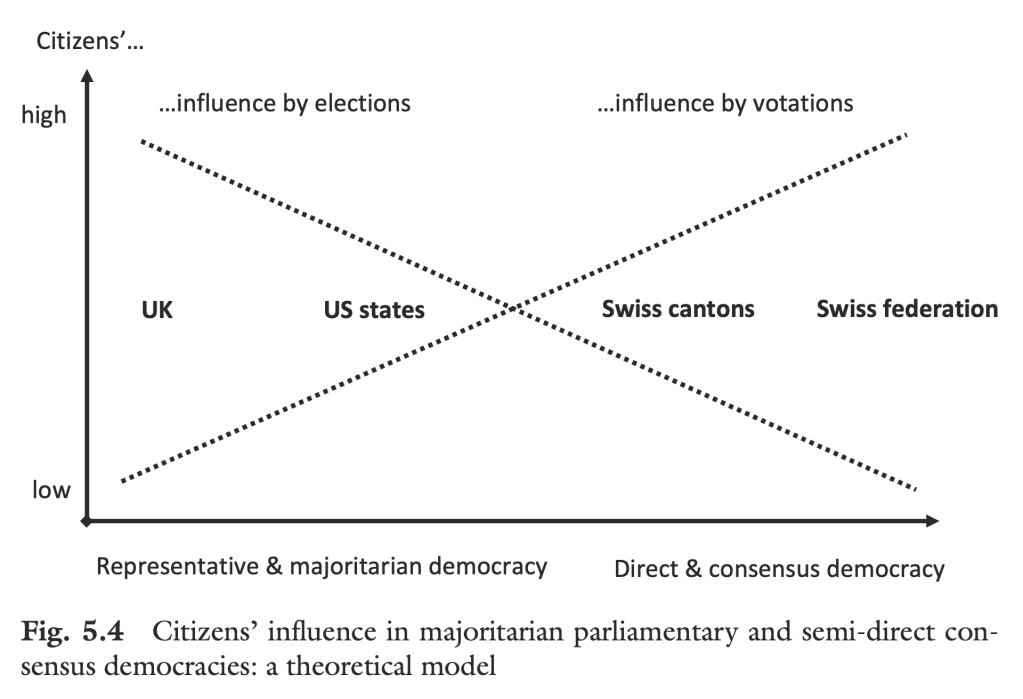

As a starting point, here’s a model to help compare the impact of democratic mechanisms in different countries:

The basic idea is that citizens in Switzerland have more power to influence through direct democracy mechanisms, and less power to influence through elections.

This is relevant if you think elections have fundamental vulnerabilities, as Ken Cloke tries to show, and I (now) accept.

One key takeaway from the book for me — and this is very basic indeed — is that the electoral democracies I am used to are “just one way” of doing democracy. There are many other mechanisms and levers we can experiment with.

On Federalism

Quoting Denis de Rougemont:

As it happens, the words federalism and federation are understood in two very different ways in the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland. In German, Confederation means Bund, which means union, evoking especially the idea of centralisation. In Swiss Romande, on the contrary, those who profess federalism are actually the jealous defenders of cantonal autonomy against centralisation. For some, therefore, to federate simply means to unite. For others, to be federalist simply means to protect freedom at home.

Both are wrong, because each is only half right. True federalism consists neither only in the union of the cantons, nor only in their complete autonomy. It consists in the continuously adjusted balance between the autonomy of the regions and their union. It consists in the perpetual combination of these two opposing yet mutually reinforcing forces.

So, federalism is a dialectical synthesis of the Whole and the Parts.

Theory of Multicultural Democracy

On the role of Swiss political institutions:

Their role was fundamental in uniting territorial communities of four different languages, two different religions, and many more different regional histories. What is more, political institutions were able to turn the disadvantages of cultural diversity—such as fragmentation and conflict—into advantages such as experimentation and solidarity. Key to this process was political integration and a particular way of dealing with conflicts and problems in a peaceful, democratic manner.

“The only way out is through”

This is a theme. When you have some fundamental differences (like language and religion), the options are usually:

- Kill the other side (genocide) and force them to leave (exodus)

- Convert the other side (crusade)

- Work together

They chose working together through:

political integration and … dealing with conflicts and problems in a peaceful, democratic manner

The constitutional framework explicitly created a multicultural state:

According to the Constitution of 1848, the Federation consisted “of the peoples (Völkerschaften) of the cantons.” In contrast to the unification of Germany or Italy, which happened in the same period, the concept of the state was thus not based on the same culture, religion, or language of its people, but on the same citizenship of the different peoples of the cantons. Switzerland therefore represents a political or civic — not a cultural or ethnic — nation.

This is important! Switzerland was never based on one origin or ethnicity, but instead included the two bitter enemies of the time, Protestants and Catholics.

Of course, they didn’t have to deal with racism, which could have been a very big factor to deal with. But it’s worth remembering how bitter and murderous the Catholic / Protestant split was at the time.

Of course, without common ethnicity or religion, they needed something else:

Successful nation-building needs cultural cement: the development of collective identity. Unlike nations such as France, Germany, or Italy, Switzerland could not rely on one common culture, language, or ethnicity, which were the prevailing bases of European nation-building in the nineteenth century. Therefore, it may have been difficult to find a common thread to bind together people from different cantons and thus identify themselves as ‘Swiss’. However, the development of patterns of collective identity relied on ‘civic’ elements such as national symbols, shared history, common myths, and finally the new federal polity.

It’s hard for me to read this without reflecting on the current political situation in the US. What if what broke down is deeper than politics, and even conflict resolution, but just the lack of a coherent national identity. Maybe we need some nation-building.

The role of the army in national identity (and it’s effect on womens’ rights):

The fact that all men are legally bound to serve in the army is not only a means of social integration. Until 1971, when voting was the privilege of male citizens only, the duty of serving in the army was considered to be correlative with having political rights—and was used as an argument against women’s suffrage. The ideology of all male citizens defending their country, and identifying with this task, was said to be the ‘cement’ of Swiss society, especially during World War II.

Inherent problem in representative democracy for minorities of any kind:

Democracy is founded on the principle of ‘one person, one vote’ and on the rule of the majority, which together make collective decisions binding for all. But is it defensible that a sizeable minority with different opinions and interests should have to comply with the decisions of the majority? If a society is deeply divided by such cultural or religious cleavages, democracy alone cannot help the problem of ‘frozen’ or ‘eternal’ minority or majority positions: the minority, which under pure ‘one citizen, one vote’ rules can never win, is likely to be frustrated and discriminated against.

…which is bad for stability. So, how do contentious and long-running minority-related questions get resolved?

The historic cultural conflict between Catholics and Protestants has by now faded away. Many of the issues were settled by the establishment of a modern, liberal democracy, which reduced the direct influence of religious organisations on the state. However, the more than four generations during which federalism permitted ‘in-between’ solutions to these conflicts needs to be noted. Thus, cultural issues were less ‘settled’ than given time to cool down.

So one answer is just “wait and let people marry so their cultural baggage becomes less important”. But another is that:

federalism permitted ‘in-between’ solutions to these conflicts

This would work well if the minorities were geographically based in different states/cantons. If not, federalism wouldn’t really help.

Institutional factors that favor multicultural integration:

A non-ethnic concept of the state, federalism, proportional representation, and other mechanisms of political power-sharing.

Pressure from the outside also helps foster national unity, provided it does not lead to armed intervention by a foreign power. All these factors were present in the Swiss case…

Switzerland also benefited from the Right Kind of cleavages:

One particular condition which can be decisive for the success or failure of political integration is cross-cuttingness. Cleavages related to religion, language, and the economy can be territorially overlapping or cross-cutting. When cleavages overlap, it means that a linguistic minority is also a religious minority and belongs to the poorer social strata of a society. If cleavages are cross-cutting, minorities are split into different groups. For instance, one part of the linguistic minority belongs to the religious majority, while another belongs to the religious minority.

From a theoretical point of view, it is evident that in this case, integration has better chances: a linguistic minority feels less discriminated against and may even be rewarded by integration if it is part of the religious majority. In situations of overlapping cleavages, however, the same group may suffer from multiple discrimination, which creates a much higher potential for grievances and ultimately political conflict (see also Steiner 1990).

Importantly, this also operates on a personal level:

Most Swiss cultural groups have experience with being part of both a minority and a majority. This has been very important for the development of a culture of tolerance and pluralism.

Power Sharing

The Swiss government has 3 main branches.

The legislative branch (The Federal Assembly) officially has most of the power, and is elected directly by the citizens. There are two bodies (bicameral) that have equal powers. One has a number of members according to population (like the US House of Representatives), and one has 2 members per canton (like the US Senate). They often meet in joint session for certain types of votes.

The Federal Assembly elects the members of the executive and judicial branches.

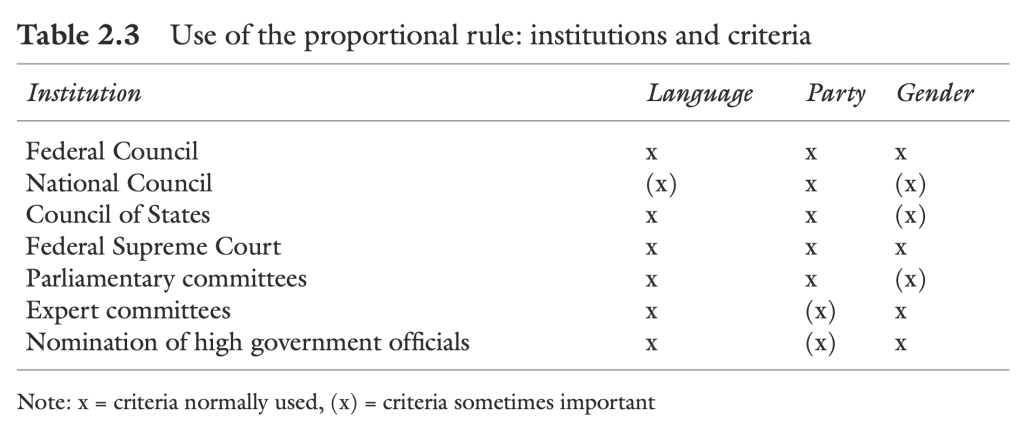

Explicit power sharing in the executive and judicial branches guarantee proportional representation:

Federal Council: The supreme executive and governing authority of the Swiss federation. Its composition mirrors power-sharing between different parties and cultures: the seven members of the Federal Council are representatives of four different political parties (in basically the same composition since 1959: three bourgeois centre-right and one left-wing party). An unwritten law requires that at least two members come from French- or Italian-speaking regions.

The Council acts as a collegiate body. There is no role of prime minister with prerogatives over the other members of cabinet; thus, most decisions come from and are underwritten by the Council as a whole. One of the seven serves as president of the federation. By custom, this function is carried out by a different member each year. The president has no special political privileges, only formal duties.

Each federal councillor heads one of the seven ministries (called departments): Foreign Affairs; Home Affairs; Justice and Police; Defence, Civil Protection and Sports; Finance; Economic Affairs, Education and Research; and Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications. The federal administration, located mostly in Bern, has a staff of about 38,000 civil servants and employees—the army, national rail, and postal services excluded.

So they executive branch has seven leaders, and to make decisions they work together instead of voting to over-rule each other.

Federal Tribunal: The Federal Supreme Court acts as the final court of appeal in cases coming from cantonal courts and involving federal law. Thus, the Court acts in all areas of Swiss law but in very different functions, depending on the specificity of the case. The Court also decides on conflicts between the federation and the cantons and on conflicts among the latter. It is empowered to review all legislative and executive acts of the cantons and guarantees the constitutional rights of the citizens.

However, the Court does not have the power, either directly or by implication, to rule on the constitutionality of federal laws… The Federal Assembly elects all judges for a term of office of six years. The composition of the Supreme Court complies with both cultural and partisan proportionality: all three state languages, as well as the most important political parties, are adequately represented.

So, we’re talking about an informal (but “strongly enforced”) quota system for the 2 branches of government that are not directly elected.

An unwritten rule says that two of the seven members of the Federal Council should be of French- or Italian-speaking origin, and over time, this has been well observed (Giudici and Stojanovic 2016). In governmental expert and parliamentary committees, too, linguistic proportions are observed more than any other proportional rule. Complaints about ‘German predominance’—more common among French- than Italian-speakers—are not well founded when looking at federal personnel statistics: at all levels of government, proportionality is observed to a high degree.

This “proportional” nature of Swiss democracy is one of its key characteristics.

However, in contrast to many other countries, Swiss quotas are not defined as hard legal rules. While some of them are written as general regulations in law, most are informal—that is, they are obeyed as a political custom. This allows for flexibility under concrete circumstances… General regulations and informal quotas can have astonishing results for the fair representation of different cultural groups.

This is one of the things the authors mean by power-sharing:

Conflict resolution in Switzerland relies very much on power-sharing rather than winner-take-all approaches. [The proportionality rule] is a universal key to power-sharing in a double sense: it opens many doors to political participation for existing actors, and it can be used by new groups arising from new cleavages.

One can imagine there are cultural factors that lead to acceptance or rejection of this sort of institution. Why did power-sharing and cooperate work well in the Swiss case?

As small societies, the cantons were unable to develop complex regimes. Most lacked the resources to build up professional bureaucracies and to back the modern form of ‘rational power’ of the state. Especially in rural regions, public works—such as building roads or aqueducts in the Valais canton—were done on a community basis: every adult man was obliged to work for several days or weeks a year for the common good (Niederer 1965).

In addition, many economic activities—farming in rural regions and crafts in the cities—were bound up in organisations which required collective decision-making. This, and the mutual dependence of people in small societies, promoted communalism. That was also reflected in the slogans used in the democratic revolutions in the cantons during the nineteenth century, when calls for the ‘sovereignty of the people’ became louder and louder (e.g. Meuwly 2018, ch. 5).

Basically, they were used to working together and sharing power.

Direct Democracy

Direct democracy options overview:

Besides electing their parliament, the Swiss voters are provided with three important instruments of direct democracy: the popular initiative, the mandatory referendum, and the facultative referendum.

The popular initiative is a formal proposition which demands a constitutional amendment. It must be submitted to the vote of the people and cantons if the proposition is signed by at least 100,000 citizens within 18 months. Before the vote, the Federal Council and the Federal Assembly give non-binding advice on whether the proposal should be accepted or rejected and occasionally formulate a counterproposal.

The mandatory referendum obliges parliament to submit every amendment of the Federal Constitution and important international treaties to the approval of a majority of cantons and the people.

The facultative referendum provides 50,000 citizens or eight cantons with the option to challenge any Act of Parliament within 100 days of its publication. If that quorum is reached, the Act is submitted to a binding vote, with a simple popular majority deciding on approval or rejection.

More on obligatory reefer:

All proposals for constitutional amendments and important international treaties are subject to an obligatory referendum. This requires a double majority of the Swiss people and the cantons, thus offering a kind of federal participation (see Chap. 3). The obligatory referendum is relatively frequent. Since Article 3 of the Constitution leaves all powers to the cantons unless specifically delegated to the federation, the authorities have to propose an amendment for every major new responsibility undertaken at national level.

This has happened successfully 140 times since 1848. The document is ALIVE. Which allows the imperfections of democracy to be slowly smoothed over, as the years progress.

More on legislative reefer:

Most parliamentary acts and regulations are subject to an optional (or facultative) referendum. In these cases, a parliamentary decision becomes law unless 50,000 citizens or eight cantons, within 100 days, demand the holding of a popular vote. If a popular vote is held, a simple majority of the voting people decides whether the bill is approved or rejected, the wishes of the cantons being irrelevant.

And more on popular initiative:

One hundred thousand citizens can, by signing up to a formal proposition, demand a constitutional amendment and/or propose the revision or removal of an existing provision. The proposition can be expressed as a fully formulated text or in general terms, upon which the Federal Assembly can then make a formal proposition. After signatures have been collected successfully, the initiative is discussed by the Federal Council and parliament, which then adopt formal positions on the proposed changes.

This can involve drawing up an alternative proposition or, if the popular initiative is couched in general terms, formulating precise propositions. Initiatives and eventual counterproposals are presented simultaneously to the people. As with all constitutional changes, acceptance requires majorities of both individual voters and cantons.

Even in this mechanism, power is still shared. The government has the time to respond and draft a counter-proposal to the initiative, so the voters don’t just have a yes/no choice, but can see different solutions to the same problem.

The Swiss have “another understanding of democracy”:

From the very beginning, this expansion of the people’s rights—not only to elect its authorities but also to vote on certain issues—led to another understanding of democracy. The model of pure representative democracy promotes the idea of an elected government and parliament who decide for the people. They are entitled to do so because they represent the people or its majority. Representative democracy requires trust in the parliamentary elite, and trust that the will of parliament is consistent with the preferences of the majority of citizens…

Distrust in government for the people led to the different idea of government through the people—that is, ‘self-rule’ in the name of the ‘sovereignty of the people.’

Okay, those are the mechanisms people have — now what’s their effect.

Most of the time the legislative referundum is not used (94% of the time). But when it is used, it works (reverses the law) about 42% of the time.

The 6% referenda cases typically represent important bills of a controversial nature and, if there is a vote, the chances of the opponents of the bill are rather high.

Therefore, the risk of an optional referendum defeat is taken seriously by federal authorities.

As Michael Jackson would say, “no one wants to be defeated.”

The perceived omnipresent risk of a referendum being organised leads the federal authorities to avoid the referendum trap by two means: first, an intensive pre-parliamentary consultation phase allows ascertaining the degree of disapproval by different actors. Second, in taking into account opposing views that are dangerous enough to bring everything down, the government then presents a legislative bill to parliament that is already a compromise backed by a large coalition of interest groups and political parties.

This is actually quite genius. The fact that people are willing to use the referendum means the government pro-actively consults people to see how much disagreement is out there, and then integrates their feedback (hopefully addressing their interests) before making the laws. And, 94% of time, they get the process right (no reefer challenge).

The existence of the mechanism forces power sharing.

We now see the direct effect of the referendum on the political process. Its status quo bias renders ‘big innovations’ unlikely. Political elites must anticipate the risk of defeat in a future referendum and are therefore bound to incremental progress. For every political project, they have to look for an oversized coalition able to defeat the veto power of possible opposition forces in a popular vote.

This leads to a second, indirect effect. The referendum has profoundly changed the Swiss way of political decision-making. The majority thus began to strike political compromises with the minority, finding solutions that did not threaten the status quo of groups capable of challenging the bill. This integrative pressure of the referendum transformed majoritarian politics into power-sharing.

And initiatives to change the constitution. They succeed ~10% of the time. What are the institutional effects?

Direct success in a popular vote is rare. But defeat does not always leave proponents with nothing. Sometimes the federal authorities pick up ideas from an initiative by drafting a counterproposal or fitting them into ongoing legislative projects. This way, the long shots of popular initiatives are transformed into proposals that are more in line with conventional wisdom and therefore stand a better chance of being accepted.

At the root of many important federal policies — from social security through the environment to equal rights — we can find a popular initiative. In this way, ideas too innovative and radical at first can later be transformed into proposals acceptable to a majority. In the long run, these indirect effects of the initiative may be even more important than rare direct success.

One of the main functions of these mechanisms is to keep the government (“the elites”) more closely tied to the median state of popular attitudes. This tends to slow down change, including progress. It’s harder to end slavery and expand civil rights to minorities with these kinds of mechanisms. Women in Switzerland got the right to vote in 1971. But it does almost guarantee a slower form of dynamism because when the median consciousness changes, there is no institutional barrier to changing the law.

Winner Take Some / Everybody Wins Something

For me, the main benefit from a conflict resolution perspective is that the decision-making process is more inclusive and continuous.

The entire political process aims at reaching a political compromise. Instead of a (small) majority that imposes its solution onto a (large) minority, we find mutual adjustment: no single winner takes all—everybody wins something. Some people attribute this behavior to a specifically ‘Swiss’ culture…From a political science perspective, however, the effect of institutions seems to be paramount. The referendum challenge, the strong influence of cantons and interest groups, as well as the multiparty system, amount to formidable veto points that simply do not allow for majority decisions and compel political actors to cooperation and compromise.

Gosh, “compelling political actors to cooperation” sounds so dreamy and responsible.

Under what conditions can everybody win something?

The idea that ‘no single winner takes all, everybody wins something’ has not always worked out. Mutual adjustments were most successful in the period leading up to the 1970s, when economic growth allowed the distribution of more public goods. In the aftermath of World War II—an experience that unified the small country—many old antagonisms between ideologies had disappeared. Optional referenda were few, and the success rate of obligatory ones was high.

Consensus became more difficult to achieve after the recession of the 1970s. With lower economic growth after the first oil crisis, there was less surplus to distribute. Political redistribution in social security and the health system became a zero-sum game: what one actor won, another lost.

This is similar to Kropotkin’s understanding of evolution: In conditions of abundance, cooperation is the rule, while in conditions of scarcity, Darwin’s logic of survival is the dominant strategy.

On Citizenship

There are three levels of citizenship in Switzerland and it’s hard to get any of them:

The Swiss are citizens of a commune, a canton, and of the federation. If foreign residents want to acquire Swiss citizenship, they have to start at the local level. Local citizenship must be acquired before applicants are granted cantonal and finally federal citizenship. The whole procedure is burdensome, costly, and time-consuming, and the highest hurdle is at the local level. Applicants must have lived in the same commune for a number of years; a local committee demands proof that the applicant speaks a Swiss language, has a basic knowledge of Swiss society and its institutions, and is socially integrated.

In smaller communes of some cantons, it is the full assembly of the citizens who ultimately decide on each application. In the late 1990s, when discrimination happened against applicants from certain countries, the Federal Supreme Court (1990) intervened, defining standards of fair procedure for the people’s assembly. While the decision was welcomed by Liberals, it was criticised by Conservatives: in their eyes, the court’s ruling was an offence against local autonomy. While the liberal view reflects a modern concept of the rule of law, the conservative position illustrates that several elements of traditional political culture are still highly valued: a bottom-up idea of the state, local autonomy, and a high degree of legitimacy through direct participation (see also Hainmueller and Hangartner 2013; Hainmueller et al. 2019).

Comparing Direct Democracy in the US and Switzlerland

Similarities:

- Uncertainty on whether direct democracy can enhance government responsiveness and accountability. For Switzerland, several characteristics of the public sector—such as the small budget of central government, limited public administration, and the modification of a proposed policy programme after its defeat in a popular vote—indicate a high level of responsiveness to the will of the people. On the other hand, the power-sharing coalition of an all-party government can also function as a political cartel and reduce responsiveness. Valid comparisons are difficult. In the US, where comparison with purely representative states is possible, Cronin notes that “few initiative, referendum, and recall states are known for corruption and discrimination. Still, it is difficult to single them out and argue persuasively that they are decidedly more responsive than those without the initiative, referendum, and recall.”

- As in Switzerland, direct democratic processes have not brought about rule by the common people. In both systems, more than 90% of important parliamentary decisions are not challenged. Popular initiatives alter and influence the political agenda but do not call into question the role of parliament as the chief lawmaker. At more than 45%, the rate of successful initiatives is higher in the American states than in the Swiss federation (10%) and its cantons (30%) (Linder and Mueller 2017, 328). But in both countries, direct democracy is marked by inequalities in participation. It is the better educated, older, and financially better-off citizens who engage more in direct democracy. The more complicated the procedure and the issues at stake, the more socially discriminatory the participation. This bias affects direct democracy, as its specific policy ramifications can be harder to grasp than simply casting a vote based on sympathy or habit. Finally, direct democracy requires citizens to get organised. Cronin states: “Direct democracy devices occasionally permit those who are motivated and interested in public policy issues to have a direct personal input by recording their vote, but this is a long way from claiming that direct democracy gives a significant voice to ordinary citizens on a regular basis.”

- Direct legislation does not produce unsound legislation or bad policy. There are strong arguments supporting this judgment, despite evidence in both countries that voters are not always well informed. In Switzerland, Kriesi (2005) shows that heuristic strategies—such as voting based on party cues—do not lead to irrational choices. Cronin argues similarly for the US. As with any majority-rule system, minorities can lose, and this risk may even be greater under direct democracy. In Switzerland, recent initiatives have raised constitutional and fundamental rights concerns (Christmann and Danaci 2012). Still, voters in direct democracies “have also shown that most of the time they will reject measures that would diminish rights, liberties, and freedoms for the less well-represented or less-organized segments of society” (Cronin 1989, 123).

- Direct democracy can influence the political agenda in favour of less well-organized interests. Environmentalists provide a good example of this in both California and Switzerland. The popular initiative broadens the political agenda and what is considered politically conceivable. However, in California, some criticize direct democracy for making the state “ungovernable,” due to the sheer number of initiatives launched by professional campaign industries serving vested interests. In Switzerland, a smaller political market and lower success rates may have limited this trend.

- Direct democracy tends to strengthen single-issue and interest groups rather than parties with broader programmes. Originally tools of social movements, direct democracy mechanisms have increasingly been used by interest groups. In the US, early victories by populists and progressives were eventually overtaken by those same elites they opposed. Cronin notes that special interest groups play large roles in both representative and direct democracy. Parliament remains best equipped to blend divergent interests into broad coalitions.

- Money is, other things being equal, the single most important factor in determining the outcome of direct legislation. Gathering signatures, running campaigns, and gaining media attention all cost money. This has led to the professionalisation of campaigns in both the US and Switzerland. In many cases, the side that spends more wins—especially in the US, where campaign finance transparency is stronger. In Switzerland, money is less determinative when issues are closely tied to voters’ personal experiences or values. However, on complex or contentious issues, money can be decisive. While volunteer activism can partially substitute for money, the financial imbalance remains a major flaw of direct democracy. First, unequal campaign spending undermines the principle of “one person, one vote.” Second, it increases the risk of deceptive messaging. These issues are not exclusive to direct democracy but are common in representative systems as well. Attempts to regulate campaign financing in both Switzerland and the US have so far been unsuccessful.

Differences:

1. In the US States, direct democracy is not an element of political power-sharing. With their two-party systems, winner-take-all elections, and relatively homogeneous majorities installed by a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant hegemony, the referendum has not become a device to permit cultural minorities—African Americans or Indigenous peoples, for instance—to gain better access to power or achieve proportional representation. Nor do we know about negotiation processes carried out in the shadow of the referendum challenge, which so much characterise Swiss decision-making. One reason for this might be that US interest groups find it much easier to exert their influence through parliamentary bargaining. Lobbyists in the US legislative tradition can try to get their interests to appear in many bills by attaching their desires as “riders” (non-germane amendments). This leads to bills that are sometimes a conglomerate of matters such as money for agriculture, schools, highway construction, and so on. Non-germane amendments facilitate the finding of “constructive majorities” between interest groups. In Switzerland—as in other European legislative traditions—these deals would not be possible because different matters must be regulated by different bills. In the US, however, they allow interest groups to influence legislation in a direct way without the “referendum threat,” which anyway is riskier. US States’ direct democracy, therefore, is neither an incentive for cooperation and power-sharing as in Switzerland, nor does it have the institutional function of political integration. In turn, because of the strong two-party system, US direct democracy has not devalued elections as the mechanism of government selection as much as in Switzerland.

2. Direct democracy in the US complements the representative polity, while in Switzerland it has transformed the entire political system. With the introduction of the referendum in 1874, Swiss political institutions—which originally followed both representative and majoritarian ideas—were completely restructured. Majoritarian democracy was transformed into a system of consensus democracy. Negotiated legislation, compromises, and permanent power-sharing became necessary if the government was to avoid defeat in referenda. This institutional transformation has not happened in the US. Especially the idea of proportional representation seems to contradict American political culture, which favours competitive elections and “clear”—that is, majority—decisions. To the Swiss observer, it seems as if representative and direct democracy in the American States were much more independent of each other. In terms of political culture, the predominant ideas in Switzerland are participation and voice, while in the US they are competition and victory.

3. In one respect, direct democracy is of much greater consequence in Switzerland than in the US. The referendum and the popular initiative are also used at national level. This distinction is important. In Switzerland, not only national but also foreign policy issues can become the object of direct democracy. The latter is even more astonishing as the Swiss Constitution was influenced by nineteenth-century doctrines which put foreign policy firmly into the hands of the executive so that it had complete autonomy in its dealings with other nations. In practice, the Federal Council is under much less parliamentary control for its foreign policy than for domestic affairs (Kälin 1986). Three constitutional amendments, passed in 1920, 1977, and 2003, introduced and further extended the people’s rights in foreign policy. Today, membership in international organisations and all international treaties implying substantial unifications of law are subject to mandatory referenda (Aubert and Mahon 2003, 1102–20; Häfelin et al. 2016). If the government should want Switzerland to become a member of a supranational organisation such as the EU or a system of collective security such as NATO, a referendum is obligatory. The Swiss polity thus empowers the people to participate in matters which used to be the sovereign right of the monarch in earlier times and which have largely remained the prerogative of the executive in most other states (Delley 1999).

How Power-Sharing Helps Resolving Conflicts in Multicultural Democracies

1. Proportional representation has a high symbolic value, favouring the development of mutual respect between different cultural groups. The self-esteem and political recognition of minority groups are an essential precondition for any rational political discourse and accommodation among elites. To promote this objective, proportional representation can be practised in many places: in the electoral system, in parliament, in the executive, in all branches of the administration, or also in the police and armed forces. Of course, proportional representation has some pitfalls. Under the conditions of one single minority or a single cleavage, there is a risk that proportional representation perpetuates societal conflict instead of cooling it down. With more than one minority and cross-cutting cleavages, however, proportionality may favour the development of non-ethnic, non-regional political parties, elites, and cultures. The evolution from a divided into a pluralist society lets old cleavages fade into the background.

2. Proportional representation favours negotiation and accommodation of conflicts whereby minorities have an effective voice. The veto power of minorities does not suspend the formal rule of majority decision. Yet, where minorities are permanently participating in decisions, formal decisions imply negotiation and accommodation, avoiding ‘winner takes all’ situations and mindsets. For example, since 1848, French-speakers have always had at least one, most often two, representatives in the seven-seat Swiss government (Giudici and Stojanović 2016, 297). The effective voice of minorities depends on two conditions. The first is mutual recognition of the different parts of the political elite. This opens the door to cooperation on a rational basis. On such a basis, solutions turning zero-sum into positive-sum games become feasible. Cooperation then is more advantageous than non-cooperation because it leaves all parts better off. The second condition is alternating, issue-specific coalitions. If today’s opponent is tomorrow’s coalition partner, both are partly dependent on each other. This favours a political culture of mutual respect and support. Empirically, under power-sharing conditions, politicians listen more to each other and give more weight to arguments of their opponents than in majoritarian situations (Bächtiger et al. 2005; Steenbergen 2009). Thus, proportional representation and power-sharing are more promising arenas for deliberative democracy.

3. Political cooperation among political elites may encourage general patterns of amicable intercultural relations. Cooperation in parliamentary and executive bodies not only promotes compromises on political issues. It may also, through frequent interaction and mutual dependency, lead to a better understanding between different cultural segments and the development of common values. This process may at first be limited to the political elites, but it can then ‘trickle down’ to larger segments of society.

4. Federalism or decentralisation may be more effective for multicultural co-existence if combined with other elements of power-sharing. Federalism may be considered a structural element of power-sharing. While restricting the power of the central government, it can guarantee autonomy for different cultural segments in territorial sub-divisions. Like basic individual rights or statutory minority rights and vetoes, federalism is an institutional mechanism restricting majority rule and limiting majority politics. Federalism as a ‘vertical’ dimension of power-sharing has its deficiencies, however, as discussed earlier in the chapter. Yet in combination with the ‘horizontal’ elements of political power-sharing, federalism and decentralisation may become more effective for minority voice and protection (Fleiner et al. 2003).

5. Consensus democracy rejects the hegemonic claims of a single group and avoids the fallacy of a monocultural nation-state. Consensus democracy is viable only under conditions of recognition of equality of all societal cultures and their groups before the state. Thus, political power-sharing requires a certain acceptance of societal and cultural pluralism. This pluralism must be instilled into the basic concept of the state: the latter must guarantee equal rights to all its citizens and renounce undue privileges for a specific culture and thus discriminate against others. In contrast to the cultural or ‘ethnic nation’, this amounts to a political or ‘civic’ conception of the nation (Verfassungspatriotismus, per Habermas 1992), where citizenship is the only qualification for membership. Such a concept is basically indifferent to the religion, language, or ethnicity of its different groups. Of course, every constitutional order is, to a certain degree, characterised by the heritage of a specific culture and its predominant values. The idea of separation of religion and the state, for instance, is realised in different ways and to different degrees in industrialised Western democracies (Madeley and Enyedi 2003). These differences may be greater still in developing societies where ligatures of religion are much stronger. Non-industrialised, traditional societies exposed to outside pressure of accelerating modernisation are sometimes even pushed toward relying on religion and other cultural traditions. However, values that symbolise a precious good for one cultural segment may be threatening for another. Such divides can be overcome only by the development of equal rights, mutual respect among all cultural groups, and the development of common—or at least neutral—values. Such a collective identity or political culture requires a high degree of indifference or impartiality on the part of state authorities towards particular cultures.

6. The development of a political culture of power-sharing takes time. A new constitution can be written in a few weeks, political parties founded, elections held, and a parliament and government installed in a few years. Successful democratisation, however, takes much longer because the consolidation of institutions, the functioning of the political process, and the appropriate behaviour of actors all necessitate the development of a democratic political culture. In times of global pressure toward accelerated modernisation and quick conflict intervention by the international community, it should not be forgotten that changes in social values, the development of common views among different segments, and cultural pluralism are processes of social integration that take time. Even more patience is needed when it comes to power-sharing as a means to overcome societal divides and accommodate deep social conflicts. The wounds of discrimination and civil war take generations to heal (Esman 1990, 14ff.). More than majoritarian settings, power-sharing institutions incite a “spirit of accommodation” (Lijphart 1968, 104), respect, trust, or even “deliberative potentials” (Steenbergen 2009, 287). But these incentives cannot be accelerated, and they are even weak and vulnerable. While trust in consensus democracy takes a long time to develop, it may quickly be destroyed by the hegemonic use of power.

7. Consensus democracy provides better chances, but still no guarantee for the peaceful resolution of conflict in multicultural societies. Peaceful conflict resolution in deeply divided societies depends on many circumstances: on the economy and resources, neighbours and foreign interests, on culture and history—and on the political institutions. The latter are just one of many factors. The only proposition here is made with regard to the type of democracy: if the choice is between majoritarian and consensus institutions, the latter provide better chances for the resolution of multicultural conflict. In theory, there are two major arguments against consensus democracy. First, it is said that the political will to share power depends to a great extent on political elites, and that power-sharing can turn into an elitist model of democracy. Second, consensus democracy can be used by hegemonic groups as a veil to hide their real power, giving minorities the opportunity to participate but no substantial influence (McRae 1990). In this case—observable, for instance, in the relations between the Jewish majority and the Arab minority in Israel—Ian Lustick (1980) speaks of a ‘control model’, with characteristics entirely different from the consensus model. Neither argument devalues the consensus model as such—but they illustrate its limits: the consensus model offers better chances or opportunities than majoritarian democracy, yet there is no guarantee that a successful political integration through mutual adjustment will actually occur.