These are my notes and quotes from Getting Past No by William Ury. I wrote my key takeaways from the book for the subscribers of my Future of Conflict series.

It’s probably worth comparing and contrasting this with Start With No by Jim Camp, which I did a couple of weeks ago.

Quotes from Getting Past No

Intro

This book is part of a trilogy:

Getting to Yes maps out the way to Yes, a mutually satisfactory agreement. Getting Past No — this book — shows how to navigate the obstacles that stand between you and Yes. For each of us encounters difficult people and difficult situations every day. The Power of a Positive No describes how to say No when it is vital to stand up and protect your core interests and values.

Part I: Getting Ready

Daniele Vare:

Diplomacy is the art of letting someone else have your way.

We tend to see negotiation as an unpleasant choice:

If we are “soft” in order to preserve the relationship, we end up, giving up our position. If we are “hard” in order to win our position, we strained the relationship or perhaps lose it altogether.

Not so! Joint problem-solving is collaboration as opposed to competition. This is essence of Getting To Yes.

We choose Joint-Problem Solving because:

It is soft on the people, hard on the problem.

5 barriers to cooperation he will deal with in this book:

- Your reaction

- Their emotion

- Their position

- Their dissatisfaction

- Their power

He outlines a strategy to breakthrough each of those barriers

The essence of the breakthrough strategy is indirect action. It requires you to do the opposite of what you naturally feel like doing in difficult situations. When the other side stonewalls or attacks, you may feel like responding in kind. Confronted with hostility, you may argue. Confronted with unreasonable positions, you may reject. Confronted with intransigence, you may push. Confronted with aggression, you may escalate. But this just leaves you frustrated, playing the other side’s game by their rules.

Your single greatest opportunity as a negotiator is to change the game. Instead of playing their way, let them have your way—the way of joint problem-solving.

As in the Japanese martial arts of judo, jujitsu, and aikido, you need to avoid pitting your strength directly against your opponent’s. Since efforts to break down the other side’s resistance usually only increase it, you try to go around their resistance. That is the way to break through.

To each barrier there is a strategy:

- Your reaction > Go To The Balcony

- Their emotion > Step to Their Side

- Their position > Reframe

- Their dissatisfaction > Build Them a Golden Bridge

- Their power > Use Power to Educate

A plea for the importance of preparation:

Before every meeting, prepare. After every meeting, assess your progress, adapt your strategy, and prepare again. The secret of effective negotiation is that simple: prepare, prepare, prepare.

Most negotiations are one or lost, even before the talking begins, depending on the quality of the preparation. There is no substitute for effective preparation. The more difficult than negotiation, the more intensive preparation needs to be.

Map of Preparation

- Interests

- Options

- Standards

- Alternatives

- Proposals

Interests

- Figure out your interests

- Why do I want what I want? (Go from positions to interests)

- Rank your interests (Don’t give up the low-priority interests!)

- Figure out their interests

Negotiation is a two-way street. You usually can’t satisfy your interests unless you also satisfy the other side’s. It is therefore just as important to understand their interests as your own. Your difficult client may be concerned about sticking within an established budget and looking good to their boss.

Ury’s Uncle Mel said:

“You know, Bill, it has taken me twenty-five years to unlearn what I learned at Harvard Law School. Because what I learned at Harvard Law School is that all that counts in life are the facts – who’s right and who’s wrong. It’s taken me twenty-five years to learn that just as important as the facts, if not more important, are people’s perceptions of those facts. Unless you understand their perspective, you’re never going to be effective at making deals or settling disputes.”

Ury:

The single most important skill in negotiation is the ability to put yourself in the other side’s shoes. If you are trying to change their thinking, you need to begin by understanding what they’re thinking is.

His primary tactics to do that are:

- Imagine the situation from their point of view

- Talk to people that know them to get to understand their point of view even better

Options

Options are creative ideas that satisfy interests.

Effective negotiators do not just divvy up a fixed pie. They first explore how to expand the pie.

Standards

How do come to agreement when interests are directly opposed? We can just use one of the party’s numbers, can we?

Payment is a great example:

Perhaps the most common method is to use a contest of wills. Each side insists on its position, trying to get the other to give in.

This leads to ego stuff, predictably:

Successful negotiators head off a contest of wills by turning the selection process into a joint search for a fair and mutually satisfactory solution. They rely heavily on fair standards independent of either side’s will.

Like: “The market”, “Comps”, “Policies”

Emotional virtue of standards:

The great virtue of standards is that, instead of one side giving into the other on a particular point, both can defer to what seems fair.

Ank: This helps the parties construct a shared idea of fairness.

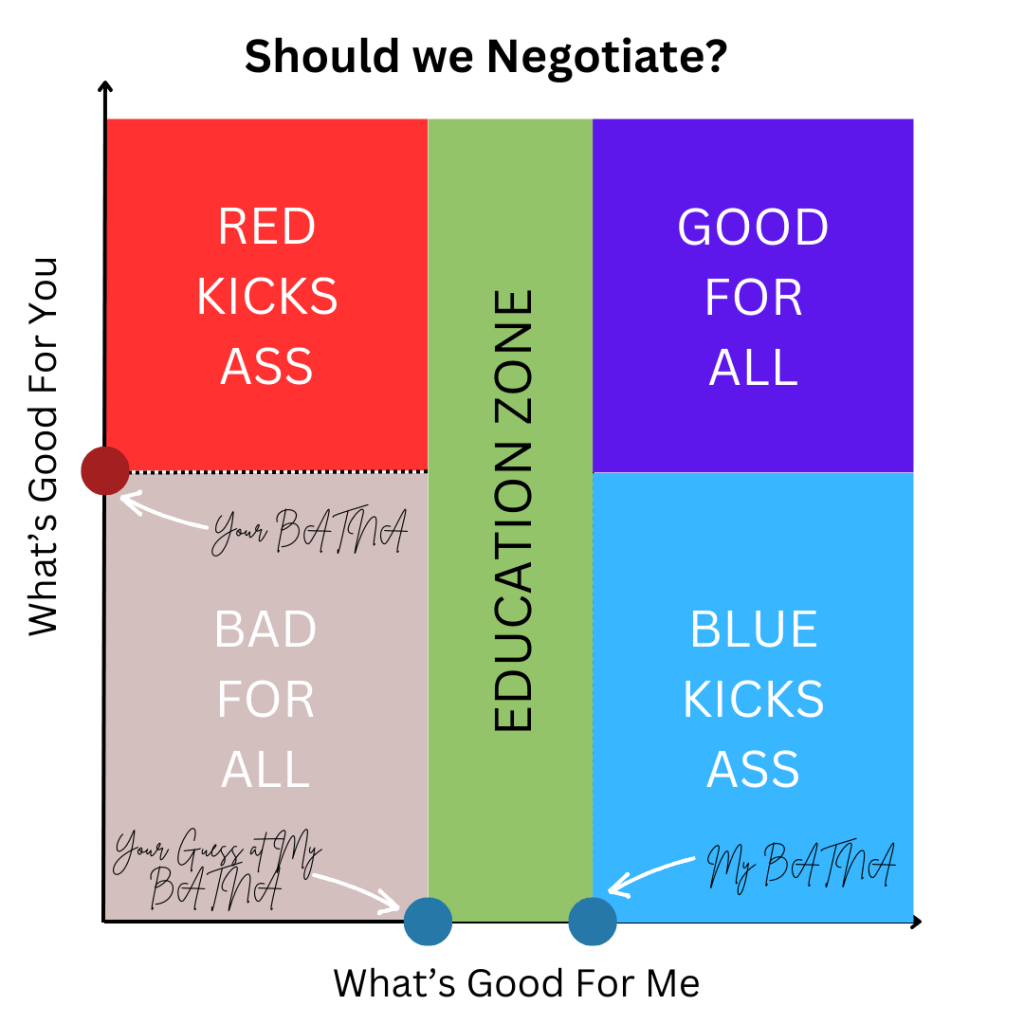

Alternatives (BATNA)

BATNA: Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (from Getting To Yes)

The purpose of negotiation is not always to reach agreement. The purpose of negotiation is to explore whether you can satisfy your interest better through an agreement then you could by pursuing your BATNA.

Three steps for your BATNA:

- Identify your BATNA

- Boost your BATNA

- Decide whether to proceed?

Identify their BATNA

If there’s nothing that is better than both BATNAs there should not be a deal.

Proposals

What distinguishes a proposal from a simple option is commitment: a proposal is a possible agreement to which you are ready to say yes.

And they can say no! And you will learn something.

To evaluate a proposal, you need to know

- What do you aspire to?

- What would you be content with?

- What could you live with?

Rehearse

Find a buddy, practice in front of them, and ask:

What did it feel like to be on the receiving end of your words?

Their domain knowledge is less important than how they feel and react.

Anticipate what tactics the other side may try and think in advance of how best to respond

Part II Using the Breakthrough Strategy

Chapter 1: Don’t React: Go To The Balcony

Three natural reactions

- Striking Back

Striking back rarely advances your immediate interest and usually damages your long-term relationships.

- Giving In

Giving in usually results in an unsatisfactory outcome. Moreover, it rewards the other side for bad behavior and gives you a reputation for weakness that they — and others — may try to exploit in the future.

- Breaking Off

A pattern of breaking off relationships means you never get anywhere because you’re always starting over.

Danger of Reacting:

In reacting, we lose sight of our interests.

The Balcony: Evaluate the conflict from far away. Gain perspective. Distancing from natural impulses and emotions. (from Getting To Yes)

But, how to suspend our natural reactions?

Name the game.

We cannot do two things at once.

If we are aware of it, we are not in it.

Three kinds of tactics:

- Stone wall: “refusal to budge”

- Attack: pressure tactics designed to intimidate

- Tricks: manipulating the data, don’t have the authority, add-on

Recognize it. It’s not actually a stone wall, it’s a “stone wall” tactic.

They’re not actually attacking you, but they want you to feel attacked

Sometimes you may have misunderstood the other person’s behavior. One of the most celebrated political images in modern times is that of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev pounding his shoe on the podium while delivering a speech at the United Nations in 1960. Everyone interpreted his histrionics as a tactic aimed at intimidating the West; a man who would pound his shoe one moment might use his nuclear weapons the next!

Thirty years later, Khrushchev’s son Sergei explained his father had had something far different in mind. Khrushchev, who had rarely been outside the Soviet Union, had heard that people in the West loved passionate political debate. So he gave his audience what he thought they wanted-he pounded his shoe to make his point. When people were shocked, no one was more surprised than Khrushchev himself. He had just been trying to look like one of the guys.

What became the very image of the irrational Russian was apparently the result of a simple cross-cultural misunderstanding.

Conclusion on naming the game:

Put on your radar, not your armor

Know your hot buttons

What are you feeling? First clue comes from the body. Stomach, heart, faces, palms, etc

Physical sensations…

They are cues we need to go to the balcony

Expect verbal attacks and don’t take them personally

Ank: “Don’t take it personally” is bad advice! If only life were so easy. But expecting attacks is a nice trick, so you can prepare.

Buy time to think

You can pause!

Thomas Jefferson:

When angry, count 10 before you speak; if very angry, 100.

Awkward. Yes. But way better than reacting.

You obviously can’t eliminate your feelings, nor do you need to do so. You only need to disconnect the automatic link between emotion and action.

You can rewind the tape!

Let me just make sure I understand what you’re saying

Or take notes:

I’m sorry I missed that can you repeat it

You can Take a Time Out!

Use an excuse. Bathroom. Coffee. Phone Call. Think about it. Caucus.

Don’t make decisions on the spot, don’t give into the pressure. Relieve the pressure.

Instead of getting mad or getting even, concentrate on getting what you want. That is what going to the balcony is all about.

Chapter 2: Don’t Argue: Step To Their Side

Do not fall into their game. Go to the balcony and then help the other side do the same.

Remember, you’re a team, even if it never feels that way.

Your challenge is to create a favorable climate in which you can negotiate.

The secret of disarming is surprise. To disarm the other side, you need to do the opposite of what they expect. If they are stonewalling, they expect you to apply pressure; if they are attacking, they expect you to resist. Do the opposite: step to their side. It disorients them and opens them up to changing their adversarial posture.

Listening

Acknowledge

Agreeing

- Listen all the way. Let them finish. Ask if they have anything more to add.

- Sayback. Paraphrase and make sure you got it right.

- Acknowledge does not mean agree. “I see what you are saying”. Acknowledge the emotions as well.

- Apologize. “I’m sorry you’re having this problem”

Project confidence when acknowledgement, it’s a stronger sentiment when it’s coming from a stronger person.

Agree without conceding: focus on all similarities first

Once they are heard and acknowledged, you can express yourself in a way that doesn’t break them.

Your views are an addition to the information available, not a contradiction.

Always good to phrase this info in the light of a mutual goal.

“Yes, And”

Use I statements

Acknowledge differences with optimism

This is all about creating a favorable climate for negotiation

You’re looking for a crack in the wall, to “trick” them into joint problem-solving

Chapter 3: Don’t Reject: Reframe

The creative and philosophical challenge is to find the game where you are partners.

You can only do that if you understand their Why.

Biden story:

Consider the following example: In 1979, the SALT II arms-control treaty was up for ratification in the U.S. Senate. To obtain the necessary two-thirds majority, the Senate leaders wanted to add an amendment, but this required Soviet assent. A young U.S. senator, Joseph R. Biden, Jr., was about to travel to Moscow, so the Senate leadership asked him to raise the question with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko.

The match in Moscow was uneven: a junior senator head to head with a hard-nosed diplomat of vast experience. Gromyko began the discussion with an eloquent hour-long disquisition on how the Soviets had always played catch-up to the Americans in the arms race. He concluded with a forceful argument for why SALT II actually favored the Americans and why, therefore, the Senate should ratify the treaty unchanged. Gromyko’s position on the proposed amendment was an unequivocal nyet.

Then it was Biden’s turn. Instead of arguing with Gromyko and taking a counterposition, he slowly and gravely said, “Mr. Gromyko, you make a very persuasive case. I agree with much of what you’ve said. When I go back to my colleagues in the Senate, however, and report what you’ve just told me, some of them—like Senator Goldwater or Senator Helms—will not be persuaded, and I’m afraid their concerns will carry weight with others.”

Biden went on to explain their worries. “You have more experience in these arms-control matters than anyone else alive. How would you advise me to respond to my colleagues’ concerns?”

Gromyko could not resist the temptation to offer advice to the inexperienced young American. He started coaching him on what he should tell the skeptical senators. One by one, Biden raised the arguments that would need to be dealt with, and Gromyko grappled with each of them. In the end, appreciating perhaps for the first time how the amendment would help win wavering votes, Gromyko reversed himself and gave his consent.

Result of reframe:

Because they are concentrating on the outcome of the negotiation, they may not even be aware that you have suddenly changed the process.

Good questions:

- Why

- Why not? — People love to criticize

- What if? — Change the game into exploring options together

- Ask for advice – They subtly gain a stake

- What makes that fair? — Understand their standards of fairness

- Silence — Give them time to propose something else

Reframe their tactics

Stone walls: Go around

- Ignore the wall and see if they repeat

- Reinterpret the wall as a reasonable aspiration

- Test the wall

Attacks: Deflect

- Ignore

- RBG was told by her mother in law: “Sometimes it’s good to be a little bit deaf”

- Reinterpret and focus on the “meat” if there is some

By choosing the more legitimate concern, you can effectively sidestep the personal attack and direct your opponents attention toward the problem

- Use attacks to focus on future

- Reframe from you and me to “we”

Tricks: Expose (this is the hardest)

- Ask slow dumb questions

- Make a reasonable request and see how they react

- Turn it to your advantage

- Look for the limitations the trick exposes, and find ways they can benefit you (or the agreement)

If there are too many tricks, you have to pop up the conversation and negotiate about the rules of the game.

Always make it easy for the other side to drop tactics. Don’t pigeonhole them as bad people or they will stick to their bad tactics.

Conclusion:

The turning point of the breakthrough method is when you change the game from positional bargaining to joint problem-solving.

Once both sides see they will benefit more by joint problem-solving, it’s more likely they will do so.

Chapter 4: Don’t Push: Build Them A Golden Bridge

Sun Tzu:

Build your opponent a golden bridge to retreat across.

Four obstacles to agreement

- Not their idea

- Unmet interests

- Fear of losing face

- Too much too fast

Frustrated by the other side’s resistance, you may be tempted to push – to cajole, to insist, and to apply pressure. But pushing may actually make it more difficult for the other side to agree.

It underscores the fact that the proposal is your idea, not theirs. It fails to address their unmet interest. It makes it harder for them to go along without appearing to be giving into your pressure.

Instead of pushing the other side toward an agreement, you need to do the opposite. You need to draw them in the direction you want them to move. You need to reframe a retreat from their position as an advance toward a better solution.

Need to look at it from their perspective.

Instead of starting from where you are, which is everyone’s natural instinct, you need to start from where the other person is in order to guide him toward an eventual agreement.

You’re helping them negotiate effectively.

Building a golden bridge means making it easier for the other side to surmount the four common obstacles to agreement. It means actively involving them in devising a solution so that it becomes their idea, not just yours. It means satisfying their unmet interests. It means helping them say face; and it means making the process of negotiation as easy as possible.

Involve the other side

Gold for every marriage and government:

Negotiation is not just a technical problem-solving exercise, but a political process in which the different parties must participate in craft and agreement together. The process is just as important as the product. You may feel frustrated the negotiations to take as long as they do, but remember that negotiation is a ritual -– a ritual of participation. People see things differently when they become involved.

Building on their ideas does not mean shortchanging in your own. It means building a bridge from their thinking back to yours. Keep in mind the 17th century Abbott, about whom the pope said, “When the conversation began he was always of my opinion, and when it ended, I was always of his.”

Satisfy Unmet Interests

To address unmet interests, you have to find them. To find them, you have to:

You have to jettison three common assumptions: that the other side is irrational and can’t be satisfied; that all they want is money; and that you can’t meet their needs without undermining yours.

Unless someone is truly crazy:

As long as there is a logical connection in their eyes between their interests and their actions, then we can influence them.

You have to see things from their perspective to figure this out.

We often assume that the other side is interested only in money or something equally tangible. We miss the intangible motivations that drive their behavior. Everyone has a need for security and a deep desire for recognition. Everyone wants to identify with some group and have control over their fate. If unmet these needs can block agreement.

Fixed pie? Low hanging fruit:

The most common way to expand the pie is to make a low cost, high benefit trade. Identify items you could give to the other side that have high benefits to them, but low cost to you. In return seek items that are high benefit to you but low cost to them.

Face Saving

Face-saving is at the core of the negotiation process. There is a popular misconception that a face-saving gesture is just a cosmetic effort made at the end of a negotiation to boost the other person’s ego. But face is much more than ego. It is shorthand for people’s self-worth, their dignity, their sense of honor, their wish to act consistently with their principles and past statements—plus, of course, their desire to look good to others. All these may be threatened if they have to change their position. Your success in persuading them to do so will depend on how well you help them save face.

Help write their victory speech

Make it easier for them to sell to skeptics on their side, like Kennedy did:

President John F. Kennedy and his advisers asked themselves this question in October 1962, as they searched for a way to make it easier for Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to withdraw Soviet missiles from Cuba. Kennedy decided to offer Khrushchev his personal pledge that the United States would not invade Cuba.

Since Kennedy had no intention of invading anyway, the promise was easy to make. But it allowed Khrushchev to announce to his constituents in the Communist world that he had successfully safeguarded the Cuban revolution from American attack. He was able to justify his decision to withdraw the missiles on the grounds that they had served their purpose.

Go slow to go fast

When it seems like too much needs to change in too short a time.

This story doesn’t strike me as relevant, but is really hilarious. It’s about a British diplomat who wanted to give some “supplies” to a British vice-consul being held prisoner by the Nazis:

He [the prison director] had the British vice-consul brought from his cell, and one by one I handed over the items: pyjamas, shirts, socks, and a toilet kit….

I then produced a bottle of sherry, explaining that the vice-consul should have it served before his luncheon. The director said nothing, but took the bottle submissively.

Next I produced a bottle of champagne which, I said, should be properly iced with the vice-consul’s dinner. The director shifted uneasily but remained silent.

Next came a bottle of gin, another of vermouth, and a cocktail shaker.

This, I explained, was for the vice-consul’s evening martini. “Now, you take one part of vermouth,” I began, turning to the director, “and four parts of gin, add plenty of ice-” But I had reached the end of my tiny steps.“Verdammt!” the director exploded. “I am willing to serve sherry and champagne and even gin to this prisoner, but he can damn well mix his own martinis.”

The idea is to make it is Easy to cross the bridge and Hard not to.

Chapter 5: Don’t Escalate: Use Power to Educate

Sun Tzu: The best general is the one who never fights.

The key mistake we make when we feel frustrated is to abandon the problem-solving game and turn to the power game instead. Making it easy to say yes, requires problem-solving negotiation; making it hard to say no requires exercising power. You don’t need to choose between the two. You can do both.

So how to use power without making things worse?

Use your power to educate the other side that the only way for them to win is for both of you to win together. Focus their attention on their interest in avoiding the negative consequences of no agreement. Don’t try to impose your terms on them. Seek instead of shape their choice so that they make a decision that isn’t their interest and yours.

Using power to educate the other side works in tandem with building them a golden bridge. The first underscores the costs of no agreement, while the second highlights the benefits of agreement. The other side faces a choice between accepting the consequences of no agreement and crossing the bridge. Your job is to keep sharpening that choice until they recognize that the best way to satisfy their interests is to cross the bridge.

Let them know the consequences

Ask reality testing questions

- What do you think will happen if we don’t agree?

- What do you think I will do?

- What will you do?

Warn don’t threaten

How can you let the other side know about your BATNA in a way that propels them to the negotiating table, not the battleground? The key lies in framing what you say as a warning rather than a threat. At first sight, a warning appears to be similar to a threat, since both convey the negative consequences of no agreement. But there is a critical, if subtle, distinction: A threat appears subjective and confrontational, while a warning appears objective and respectful.

A threat is an announcement of your intention to inflict pain, injury, or punishment on the other side. It is a negative promise. A warning, in contrast, is an advance notice of danger. A threat comes across as what you will do to them if they do not agree. A warning comes across as what will happen if agreement is not reached. A warning, in other words, puts some distance between you and your BATNA. It objectifies the consequences of no agreement so that they appear to result from the situation itself. It is easier for your opponent to bend to objective reality than to back down to you personally.

While a threat is confrontational in manner, a warning is delivered with respect. Present your information in a neutral tone and let the other side decide. The more dire the warning, the more respect you need to show.

Demonstrate the BATNA

They may not understand your BATNA or have misplaced it (see graph above). You can educate them about the reality of your BATNA by showing it.

This can be dangerous.

- Use the minimum necessary

- Do it without provoking

- Use reasonable legit means

Tap the third force! Your shared community who wants at least one of you to benefit

- Build a coalition

- Use third parties to stop attacks

- Use third parties to promote negotiation

Keep Sharpening the choice

Your power to bring the other side terms comes not from the costs you are able to impose, but from the contrast between the consequences of no agreement and the allure of the golden Bridge. Your job is to keep sharpening the contrast until they realize that the best way to satisfy their interest is to cross the bridge.

Power is dangerous and subtle

It is easy for the other side to misread your attempt to educate them through power as an attempt to defeat them. You need to reassure them constantly that your aim is mutual satisfaction, not victory. For every ounce of power you use, you need to add an ounce of conciliation.

Even when you can win, negotiate

An imposed outcome is an unstable one. Even if you have a decisive power advantage, you should think twice before lunging for victory and imposing a humiliating settlement on the other side. Not only will they resist all the more, but they may try to undermine or reverse the outcome at the first opportunity. Earlier this century, the world learned this lesson at enormous cost; an imposed peace after World War I broke down and led to World War II.

Forge a lasting agreement

You need to design an agreement that induces the other side to keep their word and protects you if they don’t. You don’t need to act distrustful; act independently of trust.

As the Arabic proverb goes:

Trust in Allah and tie up your camel.

Think of anything that can happen. Minimize your risks.

Samuel Goldwyn:

A verbal agreement isn’t worth the paper it’s written on

Build in dispute resolution from the on-set. I try to do this in my wedding ceremonies.