Future of Conflict #18: The Peru and Ecuador Peace Process, 1988

For this week’s Future of Conflict episode, I read various articles on the 1998 peace accords between Ecuador and Peru, including a chapter from Fisher and Shapiro’s Beyond Reason, a journal article from Peaceworks, and a journal article from Territorial and Boundary Disputes. (quotes and sources here)

One of my key questions going into this week was:

How are leaders’ actions impacted/limited by their constituents feelings?

This question was inspired by the movie The Human Factor about mediation during the Oslo accords. One of things that movie left me with was an awareness of how extreme elements in a conflict can directly influence the process.

Like the assassination of Yitzak Rabin. Or threats to kill Yassar Arafat if he made certain concessions.

I’ll give the briefest possible background on the conflict at play and then get to my conclusions, many of which come from an article written by Jamil Mahuad, who was President of Ecuador at the time and negotiated directly with his Peruvian counterpart, Alberto Fujimori.

Historical Background

The border conflict started in precolonial types, continued during the Spanish colonial period, and intensified in importance after Peru and Ecuador won their independence.

The conflict initially concerned three different regions and the long border between the two countries. Many of the problems were worked out over the years, and the 1941 Rio Protocol settled things for a while. The protocol also appointed four countries as “Guarantors” who could help implement the terms, militarily support demilitarization, and mediate further disagreements.

Various factors led to renewed violence in the 80’s and 90’s, and the Guarantors stepped in repeatedly to organize cease-fires and bring the parties back to the table.

In 1998, Jamil Mahaud was elected President in Ecuador, and inherited a relatively favorable climate of support to continue negotiations.

What Jamil Did

Jamil had been a student of negotiation legend Roger Fisher’s, and invited his former teacher to help with the process.

Here’s Fisher’s one-minute summary:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bZaf-3Ubaw&t=76s

The basic idea re-iterates two principles that come up again and again:

- Build positive rapport

- Establish shared goals

In this case, the two leaders had no relationship with each other and met during a high-profile international event. It was a high-stakes, televised first date.

Jamil went into the date wanting to:

- Build a relationship

- Acknowledge Fujimori’s seniority.

The second point is an interesting technique applicable to many of our conflicts (at every scale).

There are certain imbalances in every relationship. We may not want to admit them because they are not “in our favor”. But there are incredible gains to be had by accepting reality, and doing so may even strengthen our negotiating position.

In Jamil’s words:

I said, “President Fujimori, you’ve been president for eight years. I’ve been a president for four days. You have negotiated with four of my predecessors. I would like us to benefit from your extensive experience.”

I asked him, “Do you have ideas on how we might deal with this border dispute in a way that would meet the interests of both Peru and Ecuador?”

It’s crazy how textbook this is. When I do this in a personal conflict or mediation, I still have this suspicion: “Is this too transparent?”

But it turns out, authentic transparency is just a clear win.

Anyone in that situation would realize that Fujimori had way more knowledge and experience. Acknowledging that fact doesn’t mean that Jamil is going to roll over and do whatever his opponent wants — just that he’s open to whatever creative solution the other guy has in mind.

During the conversation, both leaders reiterated their commitment to end the conflict and focus on the economic health of their countries.

This led to a second, powerful, agreement:

President Fujimori and I agreed that a goal should be to have the public in each country come to see that we were working together, side by side, toward the settlement of the centuries-old boundary conflict.

The agreement is not about demilitarization or arms deals or cartography or a framework or a process: it’s about a public perception of collaboration.

Why?

This gets back to my initial question.

Whether you’re a team lead or a president, you have a constituency. That constituency has emotions and historical memory. Their way of thinking about the conflict has a certain inertia.

Making this agreement addressed three barriers Jamil saw: Belief, Participation, and Political Support.

There would have to be the popular belief that the war could be resolved. Myths are almost impossible to debunk; the intractability of the problem with Peru had deep roots in Ecuadorians’ flesh and souls.

He realized that the Ecuadorian population had a huge role to play in the conflict. If they believed it could be ended (non-militarily), he would have a vastly expanded set of options.

This belief in possibility had to translate into diverse support amongst the population.

The people had to be involved:

Making peace between Ecuador and Peru would have to be a “people’s project,” not a government issue. There would need to be a boost in participation of the people represented by any legitimate organization or group.

As did the powerful:

A formula for peace would need to be created. It would have to be acceptable for both countries and for many different sectors in each country.

Was he thinking about Rabin’s assassination? He doesn’t say, but I know I would have been.

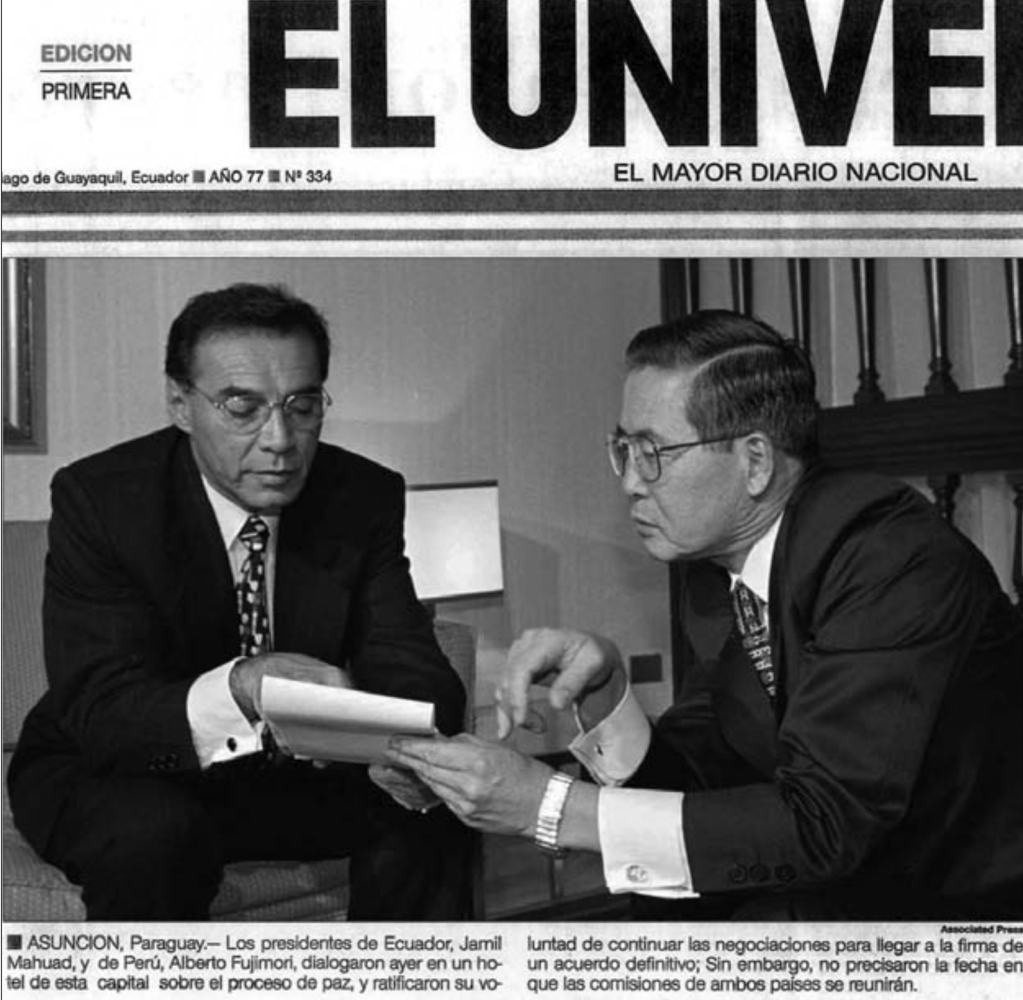

The immediate result of that agreement was a publicity stunt: a photograph of the two leaders looking at a piece of paper (probably blank) to communicate they working together, not just shaking hands.

And what it led to was a huge takeaway for me, which I call “Gaining Face”.

A huge risk in negotiation on the behalf of constituents is losing face. We don’t want to appear weak, disappoint our people, or lose our job. There is some deep pack animal behavior in here as well, I imagine.

But the two presidents leveraged the public nature of their first date to do exactly the opposite and create positive pressure towards an agreement.

In Jamil’s words:

I told Roger [Fisher] that I knew the photograph was intended to influence the public. What surprised me was the extent to which the photograph also influenced President Fujimori and me. Looking at the photograph, President Fujimori said that the public in each country would now be expecting us to settle the boundary. We had publicly undertaken that task, and we owed it to the people in each country to succeed.

The photographed created internal and external expectations for the presidents to finish the job.

The other thing this move does is create larger space of common interests. Of course the two countries have competing security and territorial interests along a shared border. There’d be no interesting conflict if they didn’t.

But now they each share a role in a different set of negotiations.

Each [of us] would have the task of bringing his own constituents to accept a settlement of the boundary. I saw my role as leading two simultaneous negotiations. One role, obviously, was as negotiator with President Fujimori. The other role, not so obvious but equally important, was my role as a negotiator with the people of Ecuador, its institutions, and representative organizations.

And, if they actual share a desire to end the conflict, they are highly incentivized to help each other in their domestic negotiations.

If I start crowing about how much I’m owning you in the current round of negotiations, it’s going to stimulate nationalist sentiment and opposition for you, and ruin things for both of us.

This reminds me of Kazu’s recent point about the Nashville Sit-Ins: when the owners capitulated and desegregated the lunch counters, the organizers of the direct-action made a point of not celebrating or releasing press releases about the victory.

Why? Because they wanted to make it as easy as possible for the white restaurant owners to keep up their side of the agreement, stay in business, and stay alive.

Along these lines, Mahaud says to Fujimori:

I proposed to him we not do anything to harm each other’s legitimacy as authorized representatives of our peoples. For instance, it would have been self-defeating to claim that a treaty was good for Ecuador because it was bad for Peru—or vice versa. On the contrary, I saw that the role of each president was to demonstrate that an agreement was good for both countries, good for the region, good for trade, good for economic development, and good for the alleviation of poverty. We needed a win-win proposition.

More precisely, each side needed its constituents to feel it was winning.

Through “win-win” emphasis (propaganda?) and transparency about the progress…

… a virtuous circle replaced the old vicious one. Negotiation became popular and openly a part of our national objectives. Participation increased. Everybody wanted to be part of the process and to express their voices.

Political actors started giving support because they understood gains were larger than risks if they represented the now popular will for peace.

Belief in a negotiated solution replaced the usual pessimism.

We can fast-forward to the mostly happy ending, where they signed peace accords seven weeks later, maintained the framework of the 1941 Rio Protocol, and had implemented everything they agreed do within a couple of years.

If there are three lessons I’m drawing from this negotiation, it’s:

- Build rapport

- Develop shared goals

- Create positive pressure (Gain Face)

The first two we’ve seen over and over. So for me, the real takeaway here is about Gaining Face.

President Mahaud did that intentionally from his first date with President Fujimori.

My sense is that he understood something about human dynamics: we want to be on somebody’s side.

This is clear with the sports world, which is very foreign to me. Many many people are very excited about essentially fake and meaningless contests, and spend huge amounts of time and money learning and participating in these events. It’s a core part of many people’s identities.

What the leaders did in this context was harness that latent desire to be “on a side” to the being on the side of the Agreement. For the previous few hundred years it was Peru vs. Ecuador. That narrative had been slowly shifting anyways, as economic crises became way more important to most citizens that an obscure territorial fight.

But the leaders were able to turn that team-oriented behavior to benefit the process, and get people excited about lasting peace.

This idea is well developed in William Ury’s The Third Side, all about our potential (and responsibility) for intervening in conflicts on the side of agreement rather than on the side of the participants.

(I did a podcast episode on it.)

Okay: The Future of Conflict.

It involves building rapport (The Relationship Is The Container).

It involves developing shared goals (Retreat to Common Ground).

And it involves building a fan base for peace, so we can Gain Face instead of losing it.

Go forth and prosper.