Future of Conflict #12: Large Group Stakeholder Dialogue

My idea for this week is to consider the conference I facilitated last week as a “text” and mine some insights from it. This process is an adapted version of a process in Ken Cloke’s Designing, Mediating, and Facilitating Large Group, Multi-Stakeholder, Consensus-Building Processes.

I don’t have a blog post of direct quotes from the book this week! Sorry.

I’ll give you a blow-by-blow of the dialogue workshop I facilitated and my understanding of the emotional and communication role of each element, with the hope that all of these elements will be relevant to other parts of your conflicts, dialogues, and lives.

Many of the stages are applicable to any kind of meeting with new people.

One goal of the dialogue was to take a group of 110 people, who were convened as a community for the first time, and help them set priorities and work plans for the next year. Another goal was to help them understand that they constituted a community in a new and powerful way.

Step 1: The Overview

The first part of the dialogue was an overview of what we were going to do together. This is an important step in any meeting where unknowns or uncertainty are present, as it allows everyone to calm down and settle into the same space together.

This might be an “energy” thing or it might be a smell thing.

But whether it’s a party with new friends, a divorce mediation, or a dialogue like this, people tend to come in a little uncertain and jumpy. And then tend to visibly relax (lowered shoulders, etc.) after 10-15 minutes.

The overview serves a few different purposes:

- It gives people information about the goals and process of the event

- It gives people a chance to leave if they’re not aligned with the goals

- It allows them a chance to calm down and settle in

- It builds the legitimacy and authority of the presenter (me, in this case)

Step 2: Diving Into Groups

A group discussion with 110 people would have a hard time being productive, inclusive, and not boring as hell. We pretty much had to divide into groups.

I chose to divide the participants into groups of 5 because:

- It’s enough that they will likely encounter at least one person they didn’t get to hang out with in the previous two days of the conference

- It’s small enough that each group would be easy to manage

- I had five good roles I could give people, so each person would have a role

The actual division of the group turned out to be quite important.

I think I have some trauma about being picked last for middle school sports, so I’m not a big fan of “captains picking teams”. And it turned out that the division was one of the most memorable parts of the activity for some of the participants.

I asked the participants to gather their affairs and told them they would be switching tables. Everybody stood up. I then told them the division would happen in silence, and a few of the organizers (3) would help them divide into five lines of equal length.

I then showed the following slide:

From that, everybody had enough to go on to silently divide into 5 equal lines in around 1 minute. It was beautiful to see and obviously to everyone there was No Way it would have gone that smoothly if people were talking.

One participant told me later:

There’s a deep lesson in how we did that without talking. I’m not sure what it is though.

The next step was for the “head” of each line (the person closest to the center of the pentagon) to “pop off”, form a group of five, and choose a faraway table.

Thus, we had an efficient mechanism for forming random groups of 5.

The division ended up serving a few purposes:

- It’s a novel experience they can tell a story about

- The movement and silence grounds them in the body and leads to a sense of wonder

- It builds more trust and authority in the presenter

- It builds self-confidence in their ability to self-organize

- It sets the tone for the event: I will set goals but not help with the execution

Step 3: Team Formation

Now that they’ve been divided into groups, I could have had them start working together. But that would miss an important stage that is essential to the success of any team: formation.

Group division is a physical step. Team formation is a relational (spiritual) step.

I gave them the following tasks to do as part of team formation:

- Introductions

- Baptism (choosing a team name)

- Roles

- Facilitator (on task)

- Scribe (on paper)

- Presenter (on message)

- Timekeeper (on time)

- Process Observer (🪞)

- Agreements

- Presentation (share team name with the group)

The point of all of this is to slow everything down and allow them to, once again, settle in to their new table and identity.

The Baptism ends up being their first consensus process. Usually it’s quite easy and funny. Most of the names ended up being inside jokes related to the conference topic they all shared.

The Roles make sure that everybody has something to contribute and be proud of, and a source of authority within the group.

The Agreements give the participants a chance to design their own culture. I could have imposed some agreements, like:

- No interruptions

- Respectful communication

- Assume positive intent

But each imposition removes an opportunity for co-creation.

(This is the wisdom of anarchism)

Ken Cloke taught me ask the following question instead:

Do you have any concerns about this conversation?

And then let each team make agreements to address their own concerns.

Finally, the Presentation is the team’s first act as a team, even if it’s simple and silly like sharing a name. They are seen as a unit for the first time, and take on the mantle of shared identity.

Step 4: Individual Answers

The main question behind the dialogue was:

What does this community need to thrive?

We answer that on three levels: Individual, Team, and Large Group.

The individual step allows for self-reflection and gives each person a chance to contribute in a way that is totally free and unconstrained. Nobody is telling them what to say or criticizing their perspective.

Then, before discussing ideas a group, every person gives their list of (5) answers to somebody at another table. This is a light version of anonymity, and it means that whatever happens next with your paper, you’re not going to be present to react to it.

It simultaneously:

- satisfies our desire to contribute,

- reduces reactivity, and

- builds trust in the larger group (like sending a letter via the post office).

Step 5: Team Answers

At this point, every person on the team is sitting with a list of 5 answers written by somebody at another table. The next goal is to come up with the team’s understanding of the top 5 pressing answers to

What does this community need to thrive?

… using the input from the other members.

This is their first big exposure to conflict and collaboration, as team members try to decipher handwriting and interpret what the writers meant. Once they’ve done that, they have to make tough choices together. (5 out of potentially 25)

Every member has a role in this process in addition to their individual contributions.

In some sense, this is the main dish of consensus, and is the step likely to have the most conflict if it weren’t properly prepared and contextualized by every step before it.

However, all of the scene-setting generally allows people to work together efficiently without taking things personally.

Step 6: Debrief

After the time alloted to making the list was up, I asked the team to give the list to the presenter to ceremonially fold in half, thereby closing the discussion.

At this point, the team switches into a short debrief, allowing the Process Observer to share any reflections they had on how the deliberations went. I instruct the team members to each share:

- One thing that worked for them

- One thing they would do differently next time

The point is to allow the group to see potential improvements without getting bogged down in blame or guilt.

(This is like Shilpa Jain’s idea of FeedForward instead of feedback)

If I instructed them to each say one thing the facilitator could have done better, I’m sure there would have been plenty of volunteers! But the whole point of the exercise is to switch people from complaint/advice to co-creation, which requires emphasizing their own power and possibility at every stage.

Step 7: Presentations

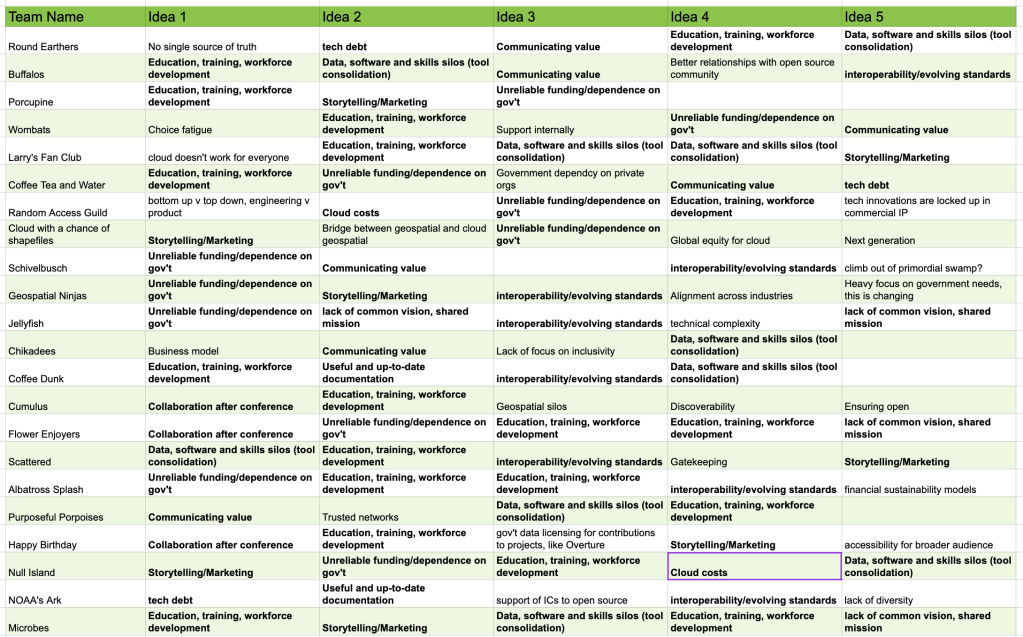

At this point, the presenter of each group goes to the podium to share their team name and top 5 ideas. Each presenter is celebrated and the answers are added to a giant matrix to be synthesized.

Every person’s input has shown up twice in the result: first as an originator (individual work) and then as a filterer (team work).

This step represents the completion of the team’s work and there is a moment for the teams to thank their members and say goodbye.

The second half of this format involves forming new teams focused on the solutions to the long list of issues the first half surfaced. Many of the steps are the same and I won’t bore you with the details.

The main takeaways from this kind of event are:

- There are ways to “set the table” to get people into collaboration instead of complaining and advice-giving

- Dialogue can work at any scale

- At least half of the time looks like it’s just “fun” or “unnecessary”, but is in fact totally essential.

Conclusion

Last week, one of the members wrote to me:

For both of those requests — couples and coworkers — points 1 and 3 apply. If we want dialogue to produce a solution instead of an argument, we can plan for that. And a big part of the planning is making sure the time and space are set up correctly.

(In this way, it’s not unlike a psychedelic voyage)